A new study is raising questions about cancer drugs that have received accelerated approval from the Food and Drug Administration.

Published in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine, the study looked at 93 oncology drugs that received accelerated approval between December 1992 and May 2017. The FDA regularly grants accelerated approval to drugs for unmet medical needs when they demonstrate efficacy on surrogate endpoints that don’t prove, but point the way to efficacy on more definitive endpoints, as long as they demonstrate more definitive efficacy in a larger clinical trial. For example, a drug might receive accelerated approval based on tumor shrinkage, but will only receive full approval when it proves it can prolong survival.

On the one hand, the study noted that the FDA has concluded the program is successful because only five of the 93 drugs have had their accelerated approvals revoked. But the study found that in confirmatory trials, only 19 drugs showed improvements in overall survival.

Another 19 drugs underwent confirmatory studies that used the same surrogate endpoints as the trials that led to accelerated approval, while another 20 used different surrogate endpoints. “So the confirmatory trials were not confirming clinical benefit but actually confirming benefit in a surrogate endpoint,” lead study author Dr. Bishal Gyawali, a researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, wrote in an email.

The study pointed in particular to Roche’s drug Avastin (bevacizumab) in the brain cancer glioblastoma. The FDA granted accelerated approval to Avastin in GBM in 2009, based on its ability to improve clinical response rates in a 167-patient Phase II study. While the drug is known to improve the time patients survive without their tumor growing, known as progression-free survival, its use in the clinic has never yielded an improvement in overall survival – the gold standard especially for a fast-growing, invariably fatal cancer like GBM. Nevertheless, despite the 437-patient confirmatory Phase III study failing to show a statistically significant improvement in overall survival, the FDA granted Avastin full approval for GBM in December 2017. Six years earlier, the agency had withdrawn Avastin’s approval in breast cancer after it failed to improve overall survival in that disease, despite improving progression-free survival.

“The FDA only approves drugs when the data received in a drug application demonstrate a favorable risk-benefit profile,” wrote FDA spokeswoman Amanda Turney in an email, adding that the agency generally does not comment on specific studies. “Patients with refractory diseases often have few or no therapeutic options and we take that into account when examining the risk-benefit profile of these drugs.”

Health Benefit Consultants, Share Your Expert Insights in Our Survey

Share some of the trends you are seeing among your clients across healthcare, including chronic conditions, behavioral health, healthcare navigation, and more.

The study authors made several policy recommendations. One would be to minimize the often lengthy times between accelerated approvals and confirmatory data by requiring that confirmatory trials be underway by the time the accelerated approval is granted. They made the same suggestion in a paper published last year in Nature as well.

“The success of the [accelerated approval] pathway lies in the fact that confirmatory studies are duly conducted in time and use clinical endpoints such as overall survival or quality of life to actually confirm benefit rather than test another surrogate measure,” Gyawali wrote in the email. “When drugs fail in confirmatory studies, quick and decisive steps must be taken to withdraw the drug from the market to prevent undue harm from unhelpful drugs.”

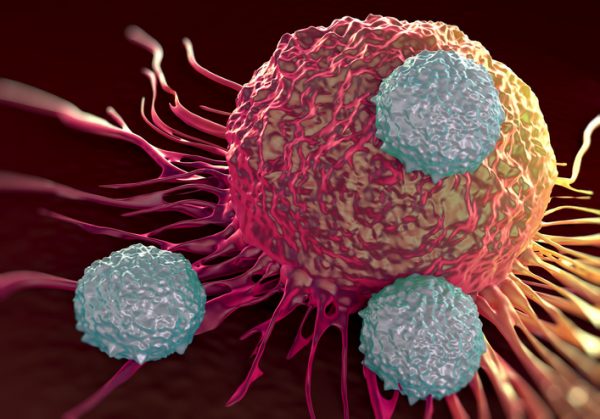

Photo: royaltystockphoto, Getty Images