The backbone of breast cancer treatment is a class of older drugs that deprive tumors of the hormones that feed their growth. Pfizer sees a new approach taken by an experimental Arvinas drug as the future of breast cancer care, and it’s committing $1 billion to the biotech in an alliance to further develop and potentially commercialize the therapy.

Behavioral Health, Interoperability and eConsent: Meeting the Demands of CMS Final Rule Compliance

In a webinar on April 16 at 1pm ET, Aneesh Chopra will moderate a discussion with executives from DocuSign, Velatura, and behavioral health providers on eConsent, health information exchange and compliance with the CMS Final Rule on interoperability.

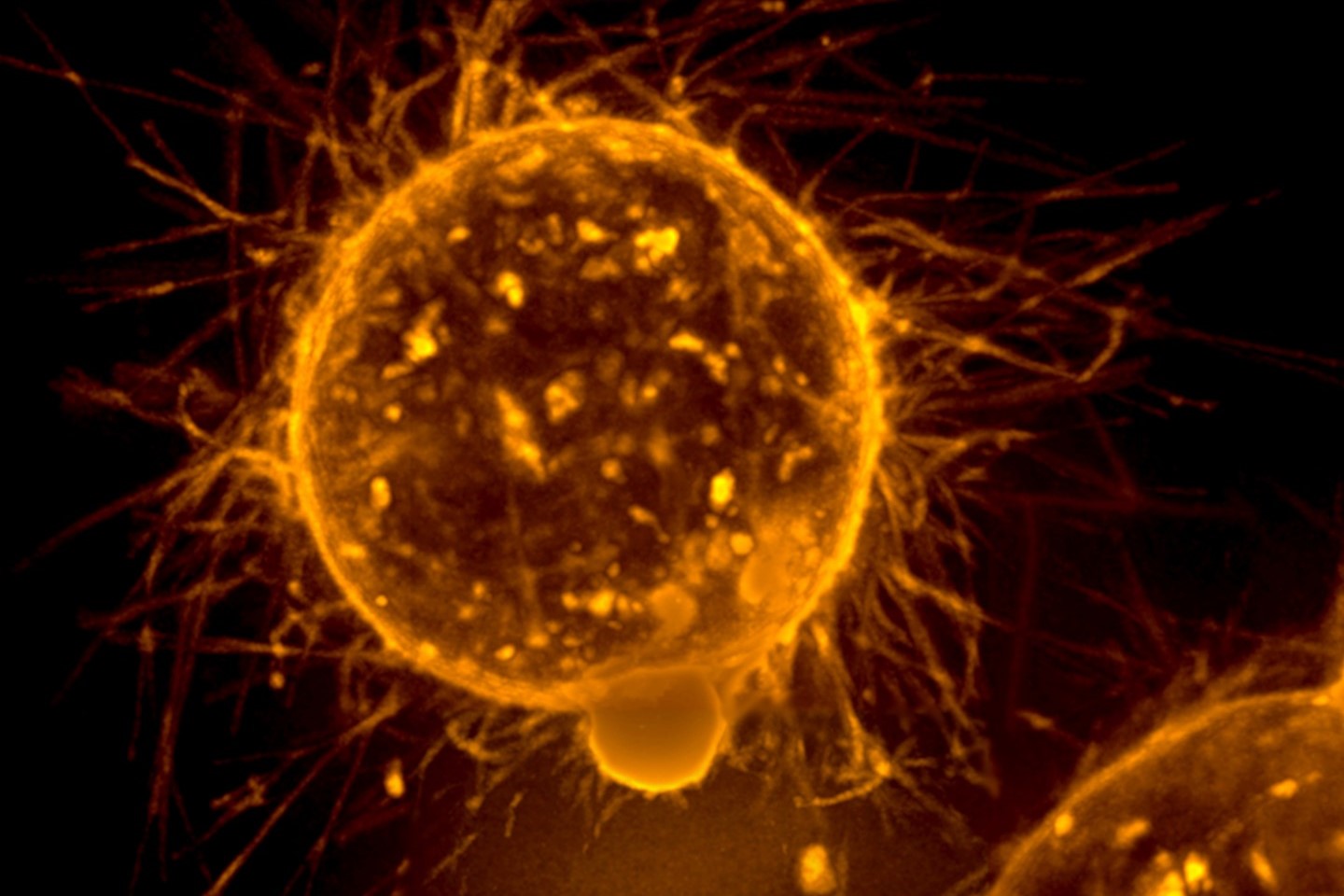

The experimental Arvinas therapy, ARV-471, is part of a new type of medicines that leverage a cell’s built-in system for disposing of old or damaged proteins as a way of getting rid of proteins that cause or contribute to disease, including cancer. Several biotech companies are developing these targeted protein degradation drugs. New Haven, Connecticut-based Arvinas is the first to bring such a drug into clinical testing for breast cancer.

“We are very interested in innovative medicines that could be potentially transformational and breakthrough medicines, and this clearly is a first-in-category medicine,” Chris Boshoff, senior vice president and chief development officer, Pfizer oncology said, speaking on a conference call Thursday.

According to terms of the deal, Pfizer will pay Arvinas $650 million up front. Separate from that payment, the pharmaceutical giant is buying $350 million worth of shares in its partner at a 30% premium to the average $101.22 price of an Arvinas share over the past 30 days, as of Monday. The purchase represents an equity stake of about 7%.

The estrogen receptor, or ER, is the primary driver of hormone receptor positive breast cancer—the most common type of breast cancer. Currently available cancer hormone therapies, such as AstraZeneca’s intramuscular injection fulvestrant, have validated the approach of degrading ER as a way of treating breast cancer, said Ron Peck, chief medical officer of Arvinas. But he added that these drugs take an indirect approach to degrading ER compared to targeted protein degradation, in which a disease-causing protein is marked for disposal by the cell’s protein disposal system. Furthermore, tests of fulvestrant have demonstrated that the approved 500 mg dose leads to greater degradation than the 250 mg dose, which in turn translates to greater efficacy.

A Deep-dive Into Specialty Pharma

A specialty drug is a class of prescription medications used to treat complex, chronic or rare medical conditions. Although this classification was originally intended to define the treatment of rare, also termed “orphan” diseases, affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US, more recently, specialty drugs have emerged as the cornerstone of treatment for chronic and complex diseases such as cancer, autoimmune conditions, diabetes, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS.

“That really is a good point of evidence that more degradation matters, and we’ve also shown that preclinically,” Peck said.

While the idea of degrading ER as a way of treating breast cancer isn’t new, drug developers have been trying to find better ways to do it. A selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD) that could be taken as a pill would have an advantage over injectable fulvestrant. Pfizer sees ARV-471 as the best of the SERDS in development. It also sees the small molecule as a potential combination partner with its blockbuster breast cancer drug Ibrance, which generated $5.4 billion in global sales last year.

Pfizer’s interest in ARV-471 was piqued last December when the biotech released preliminary data from a Phase 1 dose-escalation study. In addition to demonstrating safety and tolerability, the drug also showed strong anti-tumor activity. With those results, the company advanced the drug to Phase 1b, testing it in combination with Ibrance, a drug that works by blocking the enzymes CDK 4 and 6.

“We’re aware of the competition out there with the other investigational oral SERDs,” said Andy Schmeltz, global president and general manager of Pfizer oncology. “All have the potential to improve upon the current standard of care. We believe, based on our diligence, that ’471 is poised to be best in category, and of course the combination of ’471 with a CDK inhibitor, like Ibrance today, can potentially, downstream, in combination with other investigational CDKs in Pfizer’s portfolio, can truly be transformational.”

Arvinas CEO John Houston said that his company’s December data drew partnering interest from “a number of companies,” though he declined to say how many. He added that Arvinas was looking for a partner able to accelerate the development of ARV-471 and commercialize it broadly, while also allowing the biotech to keep the drug in its pipeline and share in the costs and risks of development.

Pfizer has already been working with Arvinas under a 2017 alliance focused on discovering targeted protein degradation drugs. That partnership is separate from the new alliance on ARV-471. Under the agreement announced Thursday, development and commercialization expenses for ARV-471 will be shared equally. If the drug is approved, Arvinas will be the marketing authorization holder in the U.S., where it will book sales. Pfizer will hold marketing authorization for the drug in the rest of the world. Profits from sales of an approved ARV-471 will be shared equally, but the deal calls for Pfizer to pay Arvinas up to $400 million in milestones tied to regulatory approval, plus up to $1 billion more in commercial milestone payments.

Arvinas has advanced ARV-471 to a Phase 2 dose expansion trial testing it in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer that is ER positive and HER2 negative. The companies said that the clinical development plan for the drug could include multiple global, pivotal studies.

Meeanwhile, the Arvinas pipeline has 12 other wholly owned targeted protein degradation drug candidates spanning cancer and neuroscience. The most advanced of those programs is ARV-110, which is in Phase 2 testing as a treatment for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Public domain image by Stuart S. Martin via the National Cancer Institute