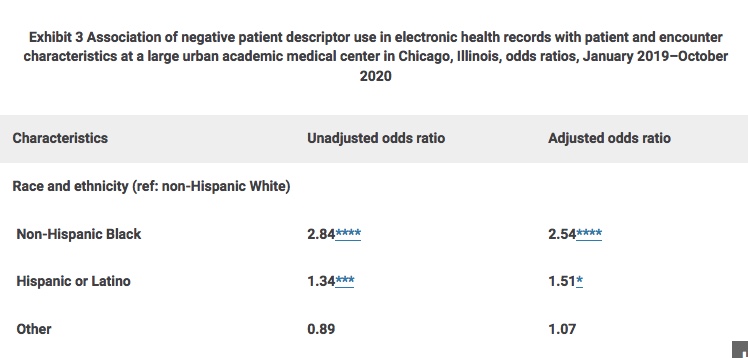

Racism is woven into many portions of society, including medical health records. A new study published in January 2022 quantified the negative patient descriptors that disproportionately impact the health records of people of color compared to their white counterparts. In fact, black patients had a negative descriptor in the history and physical notes section of their patient records at a staggering 2.54 rate than that of white patients, the report said.

The report used machine learning to comb through the electronic health records (EHRs) of 18,459 patients, controlling for health and sociodemographic characteristics. Records may label a patient as “nonadherent” or “noncompliant.” If a patient has diabetes and her numbers post meal are not controlled because the patient did not take her medication, she would be labeled as non-compliant. The study specifically searched for the terms: (non-)adherent, aggressive, agitated, angry, challenging, combative, (non-)compliant, confront, (non-)cooperative, defensive, exaggerate, hysterical, (un-)pleasant, refuse, and resist. Across the board, black patient records contained these negative descriptors more than white patient records.

What’s more, a different report found black patients are aware of these biases and it negatively impacts their care and health outcomes.

A physician with Oak Street Health, which aims to treat people over 65 through a new primary care model, believes that there are other words that can be used incorrectly and create bias.

They include “drug seeking for pain,” “angry” or “agitated,” and “refusal,” said Dr. Kevin Stephens, senior medical director at Oak Street Health in an email.

“As care providers, our medical curriculum taught us to always ask about the race of a patient as a descriptor. Oftentimes, the patient’s race has nothing to do with the issue at hand and can lead the provider to have an incorrect stereotype or bias around the patient and impact the way they treat the patient,” Stephens said.

A Deep-dive Into Specialty Pharma

A specialty drug is a class of prescription medications used to treat complex, chronic or rare medical conditions. Although this classification was originally intended to define the treatment of rare, also termed “orphan” diseases, affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US, more recently, specialty drugs have emerged as the cornerstone of treatment for chronic and complex diseases such as cancer, autoimmune conditions, diabetes, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS.

Wording is markedly different in black patients’ medical files versus their white contemporaries, even if they are battling the same condition. For example, consider a patient with sickle cell disease. Minority patients’ pain often goes under-treated, Stephens explained. Understandably, that black patient will present drug-seeking for pain tendencies as a result of sickle cell. However, it will be listed in the patient’s file as “exam inconsistent with patient reported pain.” However, for a white patient doing the same, the file often reads “patient struggles or battles with chronic pain” or “patient reports pain medications are not controlling the current condition,” according to Stephens. The report backs up this finding numerically: racism impacts medical health records.

Racial bias is prevalent across the continuum – in other words, it is not as if unfair terminology is used more often by primary care providers rather than specialists. And the best way to reduce such bias from showing up in the medical record is to create and maintain relationships.

“Continuity of care and building relationships with patients allows providers to remove biases from their care and help patients regardless of their race or location. It’s less about PCP and specialists, and more so about maintaining those ongoing relationships with patients to understand their struggles and needs for care at an individual level,” Stephens said.

Rectifying racial biases in medical files proves complicated, and requires action on both the personal, institutional, and societal levels. First, providers can consider why they utilize race to treat a patient, Stephens recommended.

“Why do we ask certain questions around race when getting to know a patient and how does that information then impact the way we think about and see patients?” Stephens challenges. “This starts in our education, and healthcare professionals at all levels must consider how we teach racial constructs in medical education.”

For example, take kidney disease. Physicians across the United States employ a race-based calculation to determine glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which is how physicians measure kidney function. However, doctors are now noticing this metric does not provide the most accurate way to determine chronic kidney disease (CKD) in patients and likely has resulted in under-diagnosing kidney disease in African Americans, according to Stephens. The National Kidney Foundation addressed this issue in September 2021, and outlined a new race-free approach to diagnose CKD in patients.

“The kidney disease and glomerular filtration rate issue was initially highlighted by medical students and is a great example of how professionals in healthcare can act on issues that are creating biases in patient treatment,” Stephens said.

Photo: Heidi de Marco/Kaiser Health News; Chart: Health Affairs Report