University of Minnesota tech transfer officials have spoken about the “Big One,” a blockbuster technology that would create or upend an industry while earning the school a hefty return for its efforts.

There’s Miromatrix Inc., which hopes to grow organs from stem cells, and VitalMedix Inc., a startup developing a drug to keep alive patients suffering from catastrophic blood loss. Ascir Inc. wants to help the military detect roadside bombs by analyzing chemical signatures. Orasi Medical thought it found a way to diagnose earlier neurological diseases like Alzheimer’s with sophisticated software.

Blockbuster technology, though, takes a lot of time and money, two things in short supply these days. Miromatrix is decades away from regenerating organs. VitalMedix filed for bankruptcy. Ascir is trying to win government grants and Orasi has switched its focus from diagnostics to drug development.

With the Rise of AI, What IP Disputes in Healthcare Are Likely to Emerge?

Munck Wilson Mandala Partner Greg Howison shared his perspective on some of the legal ramifications around AI, IP, connected devices and the data they generate, in response to emailed questions.

In the meantime, the university needs to find a way to replace income from an expiring patent on an anti-AIDS drug. A modest hit or two could go a long way.

There is one university-bred startup that hasn’t received a whole lot of attention, but perhaps offers the school a good chance of a more immediate payout. R8Scan Corp. is developing a faster, more efficient way to count, sort and analyze cells. The company, which has already raised $500,000, is seeking another $1 million over the next 12 months.

“It fits a nice niche and is very profitable,” said CEO Roger Jensen. “There are no lofty expectations that this technology will take over the world.”

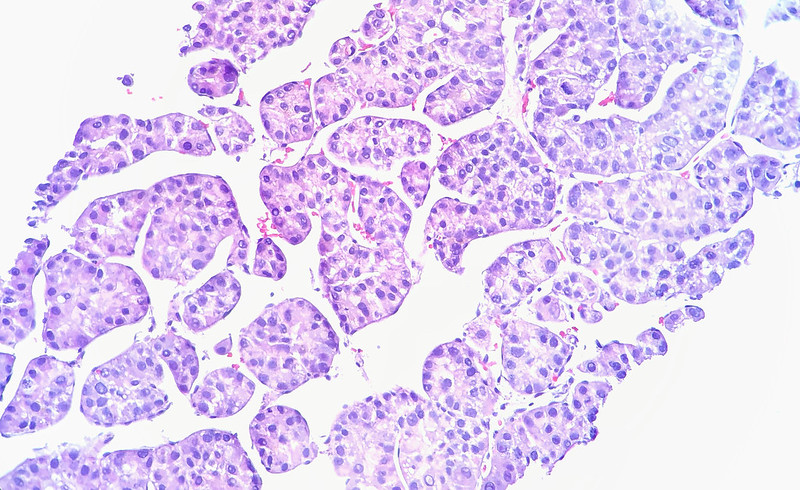

Founded in 2009, R8Scan is working to improve an established technology called flow cytometry. Scientists looking for specific properties, like DNA or protein receptors, mark cells with florescent dyes, suspend them in a fluid and pass the liquid through a laser. Sophisticated software then analyzes how the dyes react to the laser.

Today, flow cytometry is a $750 million market, dominated by companies like BD Biosciences and Amnis Corporation. University research labs, including the University of Minnesota Masonic Cancer Center, are big customers.

Jensen said R8Scan has developed a way to greatly boost the power and efficiency of flow cytometry machines. Normally, cells make a single pass through the lasers every two hours. However, Friedrich Srienc, a university professor who founded R8Scan, invented patented technology that allows batches of cells to pass back and forth through the lasers multiple times.

As a result, Jensen said researchers can capture more detailed real-time data on cells. For example, researchers can more accurately measure how chemicals impact an individual cell, which only retains a drug for a limited period of time. Drug companies in turn can predict adverse reactions and design effective treatments that patients can accept.

“This looks like a cool research technology,” said Ross Meisner, managing partner of Dymedex Consulting in St. Paul. “It appears like the customer base would be pharma companies, university research labs and bio-tech companies working to improve/refine their development processes.”

Jensen says R8Scan needs capital to further develop the software that analyzes the data. The company should create an investigational device in a year or two, he said. At its peak, R8Scan could grow into a $60 million to $70 million business, Jensen said.

Jay Schrankler, who heads the university’s Office for Technology Commercialization, believes Jensen’s estimate only reflects demand from research labs. Throw in pharma and biotech companies, and R8Scan could fetch “hundreds of millions of dollars,” he said.