There’s been much hype around President Obama’s Precision Medicine Initiative, but how realistic is it to execute successfully? A number of scientists and patient advocates met for an NIH workshop last week to flesh out President Obama’s precision medicine initiative, as reported by Science. How reasonable is it to link up the datasets of the 1 million Americans who will volunteer their genetic and healthcare information? Science writes:

It may sound straightforward, but not so, concluded the nearly 90 scientists and industry and patient representatives who met at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Still, by the end of the 2-day meeting, most of the participants seemed enthusiastically on board, if somewhat daunted by the challenges of designing what could be a project costing a billion dollars or more and lasting a decade or longer.

NIH Director Francis Collins apparently first introduced this concept back in 2004, when he directed the NIH’s genome institute – and when other countries like Estonia and the UK were advancing their own population health studies. Back then, Collins’ ideas were considered impractical and too costly, Science writes.

With the Rise of AI, What IP Disputes in Healthcare Are Likely to Emerge?

Munck Wilson Mandala Partner Greg Howison shared his perspective on some of the legal ramifications around AI, IP, connected devices and the data they generate, in response to emailed questions.

“This absolutely needs to be done. But we need to crisply articulate the goals and design it to optimize success,” cardiologist and human geneticist Sekar Kathiresan of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston told Science. “Otherwise, we are headed down a rabbit hole of spending lots of money, people questioning it left and right, and it being really wasteful.”

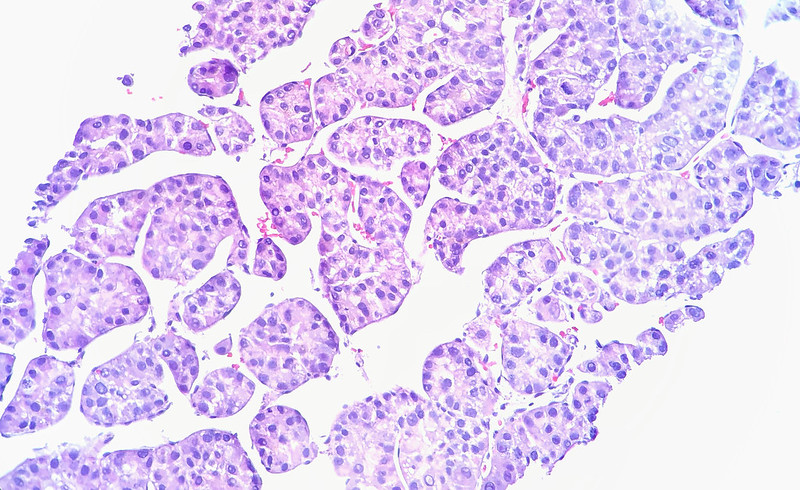

Things are different now – as illustrated by the chart above. Data’s faster, costs are lower. Precision medicine is feasible – but it’s still an uphill trek to get there. Science writes:

Still, huge questions loom: Who should be recruited? How can researchers knit together their health data? What should be the study’s overall objectives—to find rare disease genes or to test new treatments and devices?

One quick fix there, as already announced, is that the NIH will draw from existing cohort studies – such as the VA’s Million Veteran Program, which matches up DNA samples to its 20-year-old EHR. One stipulation: The NIH folks will have to contact each participant for permission to use their data – and many might choose to opt out. Also, drawing from a dataset like this one might only give researchers a limited slice of the country’s geographic, ethnic and socioeconomic diversity, Science points out. Should children be enrolled?

“If you try to do everything, you’re likely to fail,” Rory Collins, a leader at UK Biobank, told Science.

Also, participants should have some say in how their data is used, some workshop participants pointed out – but that’ll be a challenge, according to Collins. Science writes:

Some ideas could come from existing programs, such as PatientsLikeMe, a commercial Web portal that allows patients to share their health data for disease studies. Another company, 23andMe, has built a genetics research database using information from consenting customers. If older cohort studies had let patients “own” their data, “we could recruit this million person cohort almost instantaneously,” said 23andMe CEO Anne Wojcicki.

Participants were particularly excited about the mhealth contributions to precision medicine – allowing researchers to track exercise habits and exposure to environmental pollutants, as these factors aren’t readily available in EHRs.

Science concludes:

Once it was over, Collins called the workshop “historic”—and concluded that despite the unsettled issues, there are no “big showstoppers.” But NIH has a tight deadline to work out the details. The 2016 fiscal year begins in October, and assuming Congress approves a “down payment” of $130 million (which appears likely), NIH will have just 12 months to issue requests for proposals and spend the money. A working group, led by Yale University human geneticist Richard Lifton and NIH policy chief Kathy Hudson, is charged with coming up with an interim plan by September. Before then, Lifton said, “there is an enormous amount of work that remains to be done.”