The idea of a drug having to undergo clinical trials before becoming eligible for regulatory approval seems simple enough. But while dozens of drugs win approval every year from regulators like the Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency, the studies that lead to their approval are often not demographically reflective of patients in the “real world.” And with the rise of precision medicine, targeted drugs and gene therapies, lack of diversity in clinical trials can make it more challenging to get a complete picture of a drug’s safety-efficacy profile.

On June 6, the FDA issued a draft guidance on how industry could increase diversity in clinical trial populations through trial design, adjusting eligibility criteria and improving enrollment practices. This would ensure that they better reflect the general population along racial, ethnic and gender lines. Experts are divided on how much real-world effect such guidance will have even as they laud the FDA for recognizing the importance of clinical trial diversity.

What they agree on is that the status quo cannot stand. With the lack of racial and ethnic diversity in clinical trials, drugmakers are in effect marketing to Caucasians, even is the U.S. population is becoming more diverse. And that has stark implications for drug safety and efficacy.

“When you don’t have inclusion of diverse communities, you run the risk of making assumptions about drug safety and effectiveness that may not be accurate,” said Stephanie Monroe, executive director of AfricanAmericansAgainst Alzheimer’s, in an interview at the Biotechnology Innovation Organization’s annual meeting last month. “Generalizing findings of the current majority of participants – white, European men – to African-Americans, Latinos, women and others may be embracing false assumptions about the lack of differentiation between what is fast becoming the new majority.”

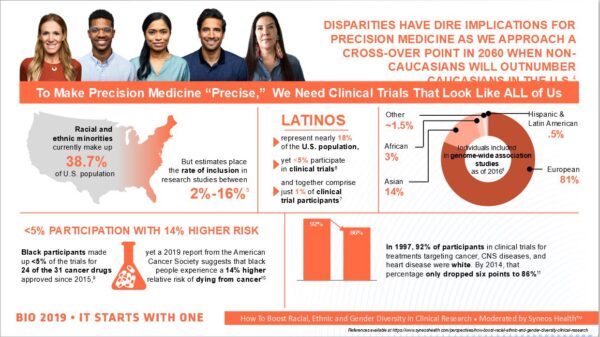

Monroe took part in a June 5 panel discussion at BIO on the topic of diversity in precision medicine that included an infographic —provided by contract research organization Syneos Health — giving a snapshot of how deficient clinical trial diversity is. While racial and ethnic minorities make up 38.7 percent of the U.S. population, their rates of inclusion in trials range from a high of 16 percent to as low as 2 percent. African-American participation rates are lower than 5 percent, despite their 14 percent greater risk of dying from cancers. Latinos make up only 1 percent of clinical trial participants, but 18 percent of the population as a whole.

The infographic presented during the BIO panel discussion (courtesy of Syneos Health)

Multiple studies illustrate why such low participation among various communities can be a problem. In 2015, a study by the FDA found that 20 percent of drugs approved since 2009 had known differences in exposure across racial and ethnic groups. And it has long been known that pharmacokinetics can differ in clinically significant ways – potentially resulting in therapeutic failure and unexpected side effects – between Caucasians and East Asians.

Gender can also play a role: Studies in recent years have shown that PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors used to treat cancers – a class that includes blockbuster drugs like Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Opdivo (nivolumab) and Merck & Co.’s Keytruda (pembrolizumab) – can be more effective in men than in women.

“In the emerging world of immunotherapy, there are genetic, racial and ethnically defined differences in immune anatomy,” said Dr. Jeff Sharman, a hematologist-oncologist in Eugene, Oregon, in a phone interview.

One example of this is T-cell receptor, or TCR therapies. Like CAR-T cells, TCRs rely on genetically modifying patients’ own immune T cells to attack tumors. But unlike CAR-Ts, they are matched to specific human leukocyte antigens, or HLAs, meaning the likelihood of their efficacy may depend on a patient’s ethnicity.

“Customized T-cell receptor therapy may be more suitable to certain racial and ethnic demographics because we have HLA-B7, but you’re not going to find that in Korea – that’s a very real difference,” he said, referring to an HLA type more common in Northern and Western European groups.Such phenomena underlie the importance of increasing diversity in clinical trial populations.

“It’s not always clear what is and isn’t generalizable, so there’s a strong interest in getting a more robust population of African-Americans or Latinos into those clinical trials so there’s more generalizable data,” Sharman said.

But despite widespread acknowledgment that lack of diversity in trials is a problem, it did not become so on purpose.

“It’s not the sponsors’ fault, and it’s not the sites’ fault either,” said Dr. Fabian Sandoval, CEO of the Washington-based Emerson Clinical Research Institute and a participant in the BIO panel, in a phone interview.

Sandoval, who also hosts the show “Tu Salud Tu Familia” (“Your Health Your Family”) on Telemundo, said the issue isn’t racism among scientists and physicians, but a constellation of cultural, economic and societal factors.

“The problem is that not everyone who is sick goes to see a doctor,” he said.

Lack of health insurance may force people to go to traditional herbalists. That action could also come from lack of awareness or education — minorities may not even know that clinical trials are occurring and are available.

Given this context, some say that such systemic problems are why the FDA’s efforts may not have too much of an effect. The challenge appears to be far deeper than any one lone guidance can address, said Arthur Caplan, a professor of bioethics at New York University.

“There are just big obstacles in a country with uneven access to healthcare,” Caplan said in a phone interview. “It’s especially difficult for recruiting minorities into research, no matter what guidance you issue.”

Lack of involvement with the healthcare system generally, underutilization of specialty care due to access and cost issues, difficulty finding transportation to reach clinical trial sites, language barriers and distrust toward medical research all contribute to minority underrepresentation in clinical trials, he said.

“These are tough problems, some of which require health reform, not guidances,” he said.

Monroe, who champions the fights of African-Americans against Alzheimers, echoed that a formal response than guidance is needed.

“Given the significant federal taxpayer, sponsor and other investments in research, more intentional focus on eliminating unnecessary exclusion criteria, addressing barriers to participation especially for diverse communities like language and lack of access to trial locations in close proximity to where these populations reside, need to be addressed more formally,” she said.

However, others were more optimistic about the effect of the FDA guidance.

Of particular interest are suggestions that studies be opened up to include pregnant women and adolescents, while trial designs could be made more adaptive, said Jeff Kozloff, CEO of TrialScope, a Jersey City, New Jersey-based clinical trial transparency and compliance firm, in a phone interview. “It’s not only improving the awareness of trials, but loosening the restrictions of who can participate and increasing the eligibility of people,” he said.

Whatever effect the draft guidance ends up happening in the long run will likely be gradual rather than something instantaneous like a light switch, Kozloff said. But TrialScope and the trial sponsors that use its services take diversity very seriously and continue to try different tactics to improve it, such as through site selection in areas with diverse populations, making participation less burdensome and adjusting inclusion and exclusion criteria, he said.

“If those criteria can start to loosen to reduce patient burden, you’re going to see a big impact down the road,” Kozloff added.

CROs – third-party outsourcing vendors whose services often include site selection and monitoring – can play a role too, potentially even more so than drug companies, Sandoval said.

While a large pharmaceutical firm can seek to boost diversity in its trials, that still only represents the efforts of one company, he said. By contrast, large CROs such as Syneos Health, Iqvia or Parexel work with a wide swath of the industry.

“Those guys all have the ears of the sponsors,” he said.

Keri McDonough, who leads advocacy and patient relations at Syneos Health, concurred.

“One of the most powerful steps a sponsor can make in this arena aligns with new FDA guidance urging sponsors and CROs to connect with patient advocates early in the drug development process,” she wrote in an email, adding that inclusive research is about good science as well as social justice. “At the heart of it, this is an access issue and most advocates are eager to close the access gaps that persist at each step of the process from research and development to commercialization.”

For their part, McDonough wrote that CROs can highlight the practical and socioeconomic barriers to greater trial diversity and the many reasons why an industry-wide concerted effort is needed in order to correct the imbalance.

“As counselors, one of our jobs is to provide clients with line of sight into what we’re hearing across the industry,” she wrote.

Universities can help as well, Sandoval added, pointing to Yale University’s Cultural Ambassadors program, which has partnered with the Junta for Progressive Action and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church to perform outreach in New Haven, Connecticut’s Latino and African-American communities in order to boost participation in clinical trials.

When reaching out to diverse communities, it’s important to have competency on the cultural and linguistic fronts, and that includes more than just bilingualism.

For example, the use of technology like wearables to enhance clinical trial participation without burdening patients with the need to travel frequently to sites requires decent connectivity and Internet services.

But Sandoval said it’s also important that they are in languages people understand – not just Spanish — but even using lay terms for medical conditions. Many communities use slang terms to discuss illness, such as among some African-American communities, where people with diabetes will say they “have sugar,” Sandoval said.

Indeed, the need for cultural sensitivity can manifest in a variety of places. For example, among the Navajo Native American tribe, discussing an illness in an older and more traditional patient can require speaking about it in the third person because telling a person they have a disease in the second person can come off like cursing them, according to a 2011 article in the trade magazine Drug Store News.

However, the diversity issue in clinical trials is solved, the rise of precision medicine and of new, cutting edge therapies makes finding a solution crucial.

“As the U.S. is really starting to build personalized healthcare and precision medicine, it would be important to build it correctly to ensure these communities are not left behind, that they’re included and that the barriers to their participation are removed,” Monroe said.

Photo: Rawpixel, Getty Images