“In the middle of this pandemic, we are building our wings after we have all jumped off the cliff,” said Dr. Karen DeSalvo, a former health IT official and Google’s new chief health officer said at at the World Medical Innovation Forum, a virtual event hosted by Panders Healthcare on Monday.

She was describing the company’s latest effort to build a contact tracing framework with competitor Apple. Two months into the Covid-19 pandemic, many parts of the U.S. response are still a work in progress. As with testing and stay-at-home orders, states are putting together fragmented responses to contact tracing. California and New York are planning to train thousands of people to do the time-consuming work of contact tracing. Other states, such as North Dakota and South Dakota, are turning to apps that use location data to help people track if they might have been exposed.

The Power of One: Redefining Healthcare with an AI-Driven Unified Platform

In a landscape where complexity has long been the norm, the power of one lies not just in unification, but in intelligence and automation.

With this hodgepodge of approaches, Apple and Google hope to create a framework for widespread contact tracing. But even if these digital tools do manage to gain enough people’s trust – and they have attempted to soothe privacy concerns with the details of their API – they simply can’t be effective enough on their own.

Getting people to opt in

The biggest obstacle to widespread digital contact tracing will be convincing enough people to opt in for it to be effective. According to a poll conducted by the Washington Post and the University of Maryland, about half of smartphone users said they would not be willing to opt in to the system designed by Apple and Google. Equally important — only 82% of the survey respondents had smartphones at all.

“The people we’re dealing with are on the other side of the digital divide. Lots of people are using the same phone,” said George Rutherford, an epidemiologist with the University of California San Francisco, who is helping train an army of 10,000 contact tracers in conjunction with the California Department of Public Health. “It’s not quite the same Singaporean model where everyone has their own phone. I just don’t see that happening in our system.”

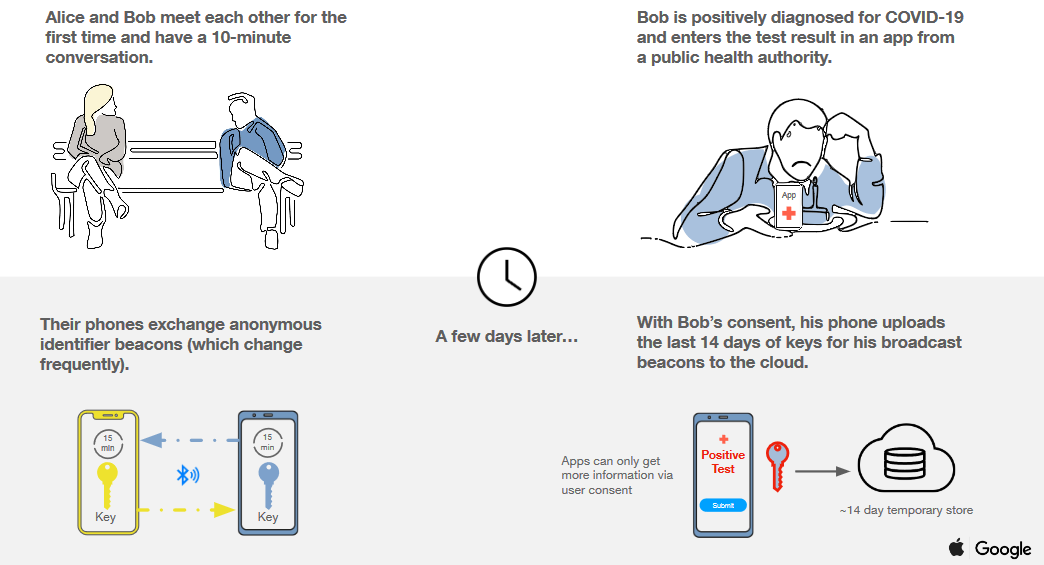

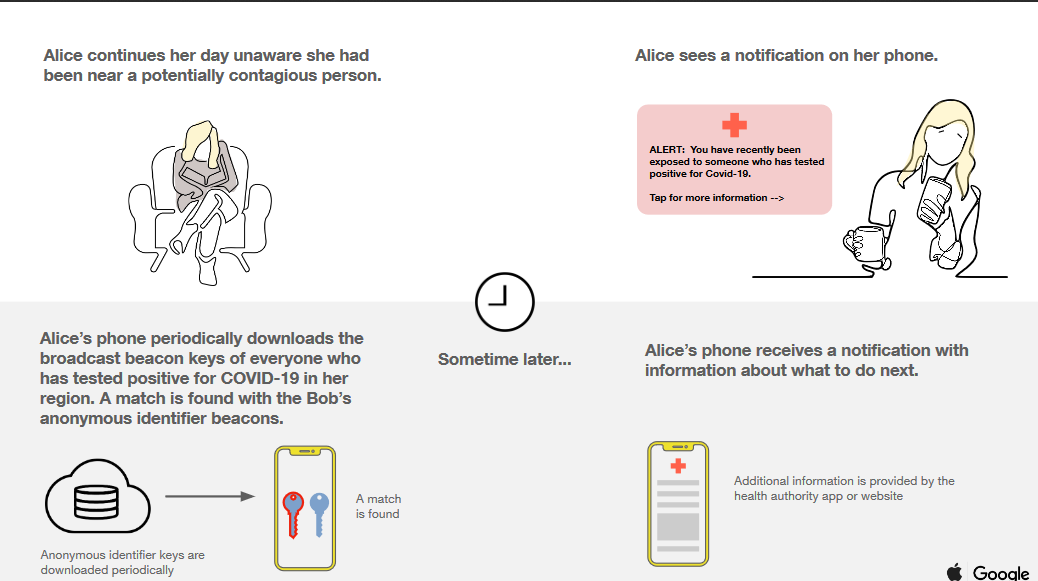

The system proposed by Apple and Google would use a Bluetooth low energy-based system to let people know if they had been less than six feet away from someone who had tested positive for Covid-19.

The two unlikely partners developed an API that they are releasing to public health authorities, which could then develop apps that would allow users to report if they had tested positive for Covid-19. Their contacts are tied to an encrypted key that changes every 15 minutes, allowing people to receive an anonymous alert if they had come into contact with someone who became ill. Both companies emphasized this system would be opt-in.

Here’s an illustration of how it would work:

Image courtesy of Apple and Google

Apple and Google have also created a list of requirements for apps to connect to this system. For example, apps must get users’ consent, and may not collect location data or diagnosis keys. If an app notifies a user that they might have been exposed to the virus, it must provide them with further guidance or resources.

Apple and Google have acknowledged that this effort is meant to augment — not replace — the work of public health authorities.

Information and empathy

The process of shoe-leather contact tracing is inherently personal, calling people, asking them how they are feeling, and if they have enough food and medications to stay inside. It’s also time-consuming, which is why California and New York are training so many people. Part of that training process involves learning to deliver the upsetting news to someone that they might have been exposed and they should self-quarantine.

“Contact tracers will be talking to people and giving bad news. And so I think that we’ve tried to give them skills and ways to talk to people and support people through what can be scary and difficult situations,” said Emily Gurley, an infectious disease epidemiologist with Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, in a press conference.

There is also some information that people can gather in an interview that would be difficult for apps to capture. For example, were there any protective measures in place, such as a mask or behind a plastic divider? What if they had been separated by a wall between two apartments?

“A lot of this stuff isn’t from drop-down menus. You have to interview people to understand what’s going on and what their risk profile is,” Rutherford said. “The other thing is, who are the contacts? If they’re working in four nursing homes, we’re going to prioritize them, as opposed to a kid that they saw playing on the street.”

Still, Rutherford is considering some technology as part of the approach. The app his team is focusing on is one that could query people’s phones to help them remember where they’ve been over the past five days. That isn’t so much a problem now, when most California cities are still under stay-at-home orders, but could be useful down the road.

“Most of the transmission we see is within households,” he said. “As we get out more and more, and people have more contacts, they’re going to be more casual contacts. It’s going to be harder to find them. The hours per contact traced is going to take more time.”

While digital tools could help augment this effort, the way they’re designed won’t necessarily integrate with the work contact tracers are doing. Since public health authorities can’t pull location data, they can’t pinpoint potential outbreak sites.

Long-term privacy implications

From from a privacy perspective, the framework developed by Apple and Google sounds good on paper. Bluetooth is generally a better option than location services for privacy and accuracy. And the tracking data will remain on users’ phones rather than being uploaded to a central location.

“This trust component is important to me, it’s important to us and it was important as we were thinking about how we could work in hotspot development,” Google’s DeSalvo said. “ I think for us it was that we wanted to use a very privacy-preserving approach — it means that we didn’t use location (data), which is noisy and not the best source of data, but rather leverage BLE as a tool to know when people are coming into close contact.”

In the first phase of the effort, users must download an app and opt in to participate. Later on, Apple and Google said they plan to build a broader Bluetooth-based functionality in their underlying systems, with users consenting to participate through a pop-up prompt. Both companies have said the tracking data will remain on the phone, and not be uploaded to a central location.

“But privacy-minded skeptics will say that they’ve heard that before with great disappointment,” Chris Bowen, chief privacy and security officer for ClearDATA, wrote in an email. “Even if you trust that these operating systems are secure and that the companies won’t offload that data from your mobile device, you have these apps on these devices that are tracking what phones you’ve been near.”

More broadly, the use of app-based tools brings up concerns about the possibility of “surveillance creep” during a pandemic.

A big part of that hesitance comes from looking at what other governments have done so far. In South Korea, the legislature gave the government authority to collect location data from people who have tested positive. That data is simply anonymized and published online, where citizens can check for possible interactions with infected people.

But the government doesn’t always do a good job anonymizing that data — one alert notified the public of a 43-year-old man in a specific district attending a sexual harassment class, according to a white paper published by the ACLU.

“Policymakers must have a realistic understanding of what data produced by individuals’ mobile phones can and cannot do,” the ACLU warned. “As always, there is a danger that simplistic understandings of how technology works will lead to investments that do little good, or are actually counterproductive, and that invade privacy without producing commensurate benefit.”

China is requiring its citizens to install an app on their phones, which would scan QR codes at entrances to taxis, subway stations, buildings and the like. And in Israel, the government is reportedly using cell phone location records to monitor proximity. One woman was issued a quarantine order because she waved at her boyfriend, who had Covid-19, from outside of his apartment building, according to the ACLU.

“Many privacy experts, myself included, shuddered to contemplate that privacy expectations during and after the pandemic could tilt in that direction,” Bowen wrote. “There’s a huge trust issue here, which is unfortunate but justified. … This pandemic provides governments and technology companies an opportunity to earn back trust. The most important question is, will they?”

Photo credit: Zhuyufang, Getty Images