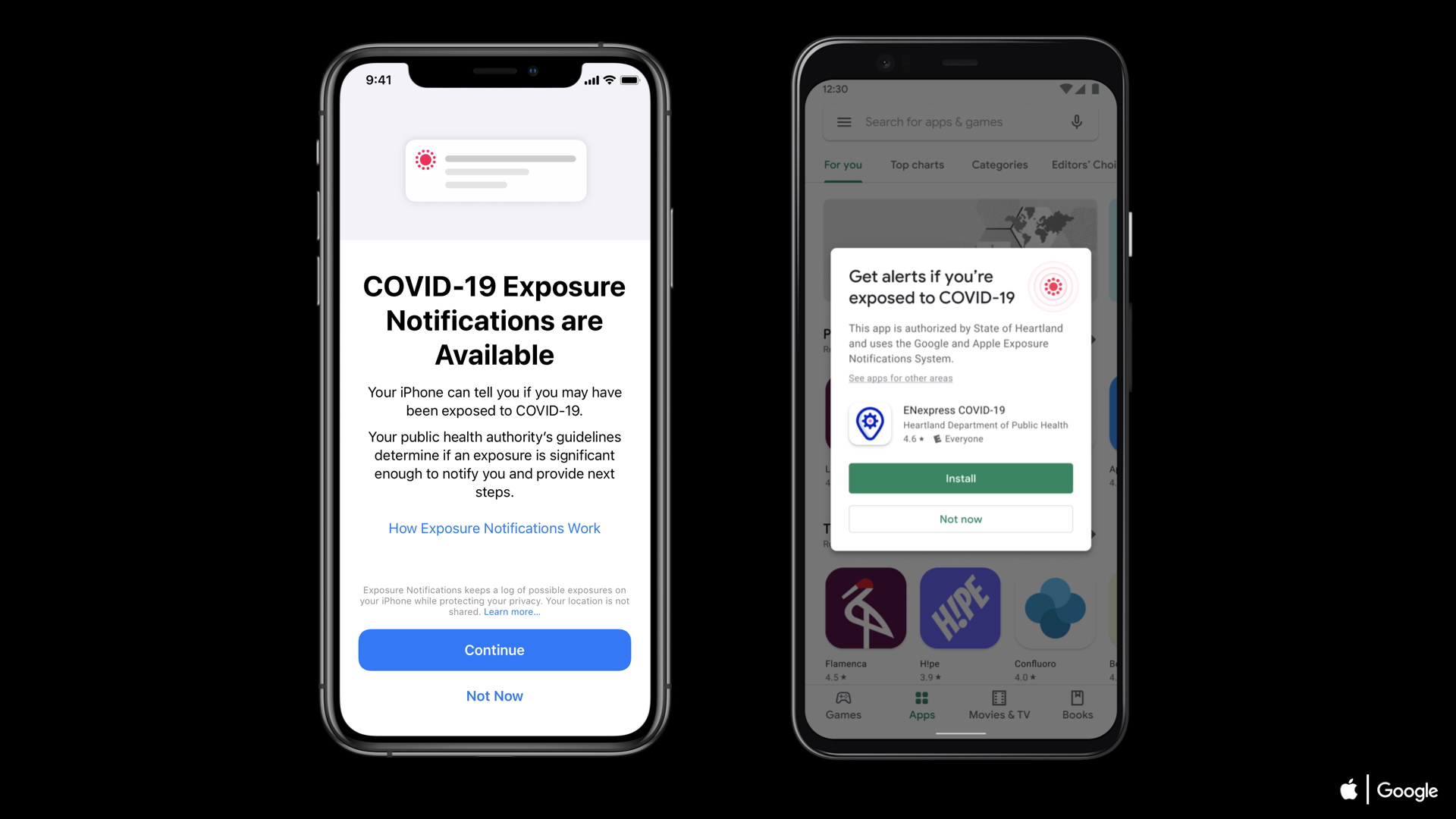

An update to Apple and Google’s exposure notification system would no longer require public health authorities to develop their own contact-tracing apps. Photo credit: Apple and Google

Back in April, Apple and Google announced to much fanfare that they would develop a Covid-19 contact tracing system. The two tech rivals proposed using Bluetooth to notify smartphone users if they had been within six feet of someone who tested positive for Covid-19, using an app developed by their local public health agency.

But so far, only six states have contact tracing apps using this framework: Virginia, North Dakota, Wyoming, Alabama, Arizona and Nevada.

Navigating The Right Steps For Your Healthcare Startup

This webinar will explore how a banking platform approach could be the resource for your company.

Now, Apple and Google are trying to make things a bit easier for public health agencies by no longer requiring them to develop their own contact tracing apps. Instead, users would be able to opt-into the exposure notification system after getting an alert on their smartphones.

“As the next step in our work with public health authorities on Exposure Notifications, we are making it easier and faster for them to use the Exposure Notifications System without the need for them to build and maintain an app,” the companies wrote in an emailed statement.

With the earlier system, public health agencies had to develop their own apps that would connect with the system. They also had to meet a list of requirements: For example, they couldn’t collect location data or diagnosis keys, and they had to get users’ consent and provide users with further guidance on what to do if they had been exposed to the virus.

Now, Apple and Google will operate a system that they call “Exposure Notifications Express” on behalf of public health authorities. They simply need information from health agencies on how residents can contact them and instructions for what users should do if they’ve been exposed to the virus.

This could help overcome one of the biggest obstacles to automated contact-tracing: getting enough people to opt-into the system for it to become effective. But it still can’t replace some of the benefits of manual-contact tracing.

For instance, an app can’t get important contextual information, such as whether both people were wearing masks, or if there was a plastic divider or another barrier between them. Contact tracers would also want to know if one of those people worked in a nursing home or another setting where they could potentially expose others to the virus.

And some features that are important from a privacy perspective — such as not being able to pull a user’s location — might be a hindrance to public health authorities looking to pinpoint potential outbreak sites.

According to a review published last month in the Lancet Digital Health, no studies have yet compared the effectiveness of automated contact tracing to manual contact tracing. The studies suggested that the majority of the population would have to use these apps for them to be effective in controlling Covid-19.

“As a result, manual contact tracing on a large scale is still likely to be required in most contexts, and there is a clear need for further research to strengthen the evidence base for automated contact tracing,” the article noted.