BMS

BMS

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) published its second-ever report on Unsupported Price Increases (UPI) last week, compiled from data supplied by SSR Health, which is part of the investment research firm SSR.

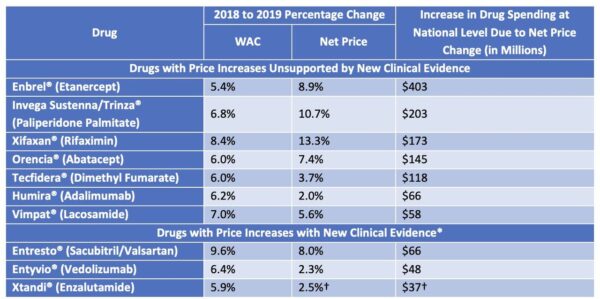

While the medical pricing watchdog found that overall spending was down from the previous year, the report highlighted 10 drugs whose prices increased. Further, it found that seven of these had price hikes that did not correspond with any newly discovered clinical benefit. ICER estimates that patients, insurers and pharmaceutical benefit managers (PBMs) were overcharged $1.2 billion in 2019, alone.

NEMT Partner Guide: Why Payers and Providers Should Choose MediDrive’s TMS

Alan Murray on improving access for medical transportation.

“These are not cherry-picked niche drugs, or some sort of outlier situation,” ICER spokesman David Whitrap said in a phone interview. “These are the costliest price increases for our country and of those ten, seven of them have no evidence for support.”

Not surprisingly, pharmaceutical companies named in the report negatively were none too pleased.

ICER published its first UPI report in October 2019, identifying a different list of seven drugs and saying their unsupported price increases cost Americans an additional $4.8 billion across the two years covered in the report, 2017 and 2018.

Given increased state-level and congressional scrutiny as well as a number of value-based contracts between states and pharmaceutical companies, drug prices have flattened, overall. But ICER does not see that as a reason to stop using clinically driven value-based analysis to determine appropriate drug costs.

“This was never intended to be some sort of broadside against the industry,” Whitrap said. “We should applaud industry as a whole for moderating their price increases over the past two years — but at the same time, just because companies A, B and C have made their industry look better as a whole, I don’t think that’s a reason we should let company D off the hook.”

Combining Economic and Clinical Research

While the first report covered the price and cost increases over that two-year period, 2020’s report solely includes 2019 price data. According to ICER, two of the drugs had clinically unsupported price increases high enough to render their inclusion in both reports: AbbVie’s Humira (adalimumab) and Biogen’s Tecfidera (dimethyl fumarate).

To compile the 132-page report, ICER first secured a list of 2019’s top 100 drugs by U.S. sales from SSR Health, part of boutique investment research firm SSR LLC. ICER excluded 67 drugs whose increase in wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) was not larger than twice the increase in the medical consumer price index (CPI) and, for the remaining 33, performed analyses to determine the increase in spending that was due to increases in net price as opposed to volume.

From that, the report assessed the 10 drugs with the highest price increases to determine if there was some new clinical finding that might justify charging more. Notably, the organization did not attempt to establish through formal cost-benefit analysis whether the price increases were justified by meeting a health-benefit price benchmark, only that new evidence existed that could justify an increase.

ICER reviewed randomized clinical trials (RCTs), high-quality comparative observational studies and large uncontrolled studies for infrequent harms. It analyzed high- and moderate-quality evidence of a substantial increase in net clinical benefit “compared with what was previously believed.” Those drugs that had evidence meeting this standard were reported as having price increases “with new clinical evidence.”

The seven drugs that were found to have unsubstantiated price hikes were:

- Amgen’s Enbrel (etanercept),

- J&J Janssen’s Invega Sustenna and Trinza (paliperidone palmitate)

- Bausch Health’s Xifaxan (rifaximin),

- Bristol Myers Squibb’s Orencia (abatacept)

- Biogen’s Tecfidera (dimethyl fumarate)

- AbbVie’s Humira (adalimumab) and

- UCB’s Vimpat (lacosamide).

Despite not having been included in the initial group, Enbrel shot up to the No. 1 position on the list after public input calling for its inclusion. This was because it had the greatest increase in impact on national drug spending — $403 million.

The three drugs for which new evidence of clinical impact aligned with price increases were Novartis’ Entresto (sacubitril and valsartan), Takeda’s Entyvio (vedolizumab) and Astellas Pharma’s Xtandi (enzalutamide).

Source: ICER

ICER contacted manufacturers of the identified top 10 drugs for early feedback on its figures for change in net price, sales volume, and overall net revenue. Given feedback from Novartis saying its drug Cosentyx had not achieved an increase in net sales, it was removed from the top 10 and Astellas’ Xtandi moved from 11th to 10th place.

Drugmakers Dispute Report’s Findings

Four of the seven companies accused of unsubstantiated price increases responded to requests for comment.

The feedback was unanimously negative.

Concerns ranged from ICER’s use of just two years for inclusion of medical evidence to support price increases, to a failure to place net price increases in the context of a rebate-based pharmaceutical industry.

“We believe ICER’s 2020 Unsupported Price Increases report is biased, selective and unreliable,” said Lainie Kelle, a Bausch Health spokeswoman, in an email. “ICER refused to consider relevant clinical, real-world and health economic evidence that supports the value of XIFAXAN as an important treatment option for several conditions.”

Bausch Health called ICER’s timeframe for inclusion of evidence “arbitrary” and “narrow,” saying it “ignores the reality of how long it takes to generate and publish pharmaceutical research.” ICER’s report relies on studies published between Jan. 1, 2018, and Dec. 31, 2019, claiming that is a sufficient look backward to call evidence “new.”

Another pharma company also rebutted ICER’s conclusion about its drug.

“In reviewing ICER’s final UPI assessment, we firmly believe that VIMPAT’s body of clinical evidence strengthens its value to patients experiencing uncontrolled seizure disorders and supports its net price,” said Allyson Funk, a UCB spokeswoman, in an email. Funk declared that UCB continually evaluates its medications’ prices to ensure they reflect the value they deliver to patients, society, and the healthcare system, and said the company will continue to study VIMPAT’s impact on managing disease.

Janssen echoed concerns about a “narrow” and time-limited literature review, saying it lacked “real-world” evidence and focused too tightly on net cost, failing to weigh factors such as patient cost and outcomes.

In an email, Janssen representative Katie Upton named ISPOR, the Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research, and ISPE, the International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering, as two research organizations that support the company’s assessment, deeming real-world evidence “critical in the accurate assessment of the value of medicines.” Upton said Janssen supports value assessment that is “patient-centric, holistic, and represents the needs of all stakeholders.”

Amgen, accused of the biggest unsupported price hikes, said that ICER did not properly analyze its data and that fault for its price hikes lies with the nature of the highly competitive drug marketplace.

“When applying ICER’s published methodology and criteria, we believe Enbrel is not qualified as having an unsupported price increase (UPI),” said Kelley Davenport, an Amgen spokeswoman, in an email. “While the ICER report acknowledged the context and the quality of the SEAM-PsA trial, their conclusion that methotrexate and etanercept have similar efficacy is inconsistent with the trial results which demonstrated superior efficacy of etanercept compared to methotrexate for the primary and key secondary endpoint in well-established psoriatic arthritis outcome measures.”

Davenport added that Amgen has raised list prices over the years in reaction to competitors’ price hikes, while offering lower net prices and higher and higher rebates to PBMs to remain covered by health plans and ensure patient access to the drug.

“If we had not done so, we believe the PBMs would have simply removed Enbrel from their formularies in favor of a competitor who provided a higher rebate to the PBM,” Davenport said. “Since Enbrel and its competitor products do not provide the same response in all patients, they are not simply interchangeable — if taken off formulary, many Enbrel patients would not have access to the medicine that they and their doctor had determined worked best for them.”

Amgen is not the only one taking note of the continual one-upmanship occurring among pharma competitors — and placing a fair share of blame on PBMs.

In a withering report issued January 14 investigating rising insulin costs, Sens. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), co-chairs of the Senate Finance Committee, found that business practices and relationships among drugmakers and PBMs have driven “skyrocketing prices.”

“This industry is anything but a free market when PBMs spur drugmakers to hike list prices in order to secure prime formulary placement and greater rebates and fees,” Grassley said in a statement.

However, Grassley and Wyden’s report would hardly consider Amgen a victim in this story.

Announcing the report, Wyden argued that “consumers are the only ones losing out in America’s broken drug pricing system, since every part of the pharmaceutical supply chain benefits from higher list prices.”

Interrogating Insulin

After a push from state regulators, ICER included insulin in its financial analysis, based on the “financial toxicity” of high list prices for uninsured patients, those with high-deductible plans, Medicare beneficiaries, and those who turn 26 and must transition from their parents’ insurance.

Indeed, though it did not interrogate insulin studies to assess whether price increases were clinically supported, ICER found that while net insulin prices overall went down, four of the 10 drugs analyzed showed wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) increase substantially higher than medical inflation overall. One drug increased with medical inflation, and four remained flat at a rate that ICER had previously deemed high. Along with the Senate Finance Committee, diabetes patient advocates are deeply concerned by this trend.

“Inventors Frederick Banting and Charles Best sold the insulin patent for a mere $1 in the 1920’s because they wanted their discovery to save lives and for insulin to be affordable and accessible to everyone who needed it,” Carol Wysham, M.D., president-elect, Endocrine Society, wrote in a position statement published January 13 in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, pushing for government action to control skyrocketing costs. “People with diabetes without full insurance are often paying increasing out-of-pocket costs for insulin resulting in many rationing their medication or skipping lifesaving doses altogether.”

Balancing Innovation and Access

ICER hopes reports such as this one will keep costs down on drugs that provide limited clinical benefit without stifling the development of pioneering new drugs. It previously championed the most expensive drug in America, Zolgensma, as priced to value, saying its $2.1 million price tag is reasonable given that it completely cures an otherwise fatal childhood disease.

“But the only way we’re going to be able to afford the Zolgensmas of the country is if we stop overpaying for drugs that do far too little for patients,” Whitrap of ICER said. “We feel there is a way to do both, here: to keep the incentives alive for innovation and new research on drugs already on the market while also stopping costly increases for drugs where there is no evidence of a new benefit.”