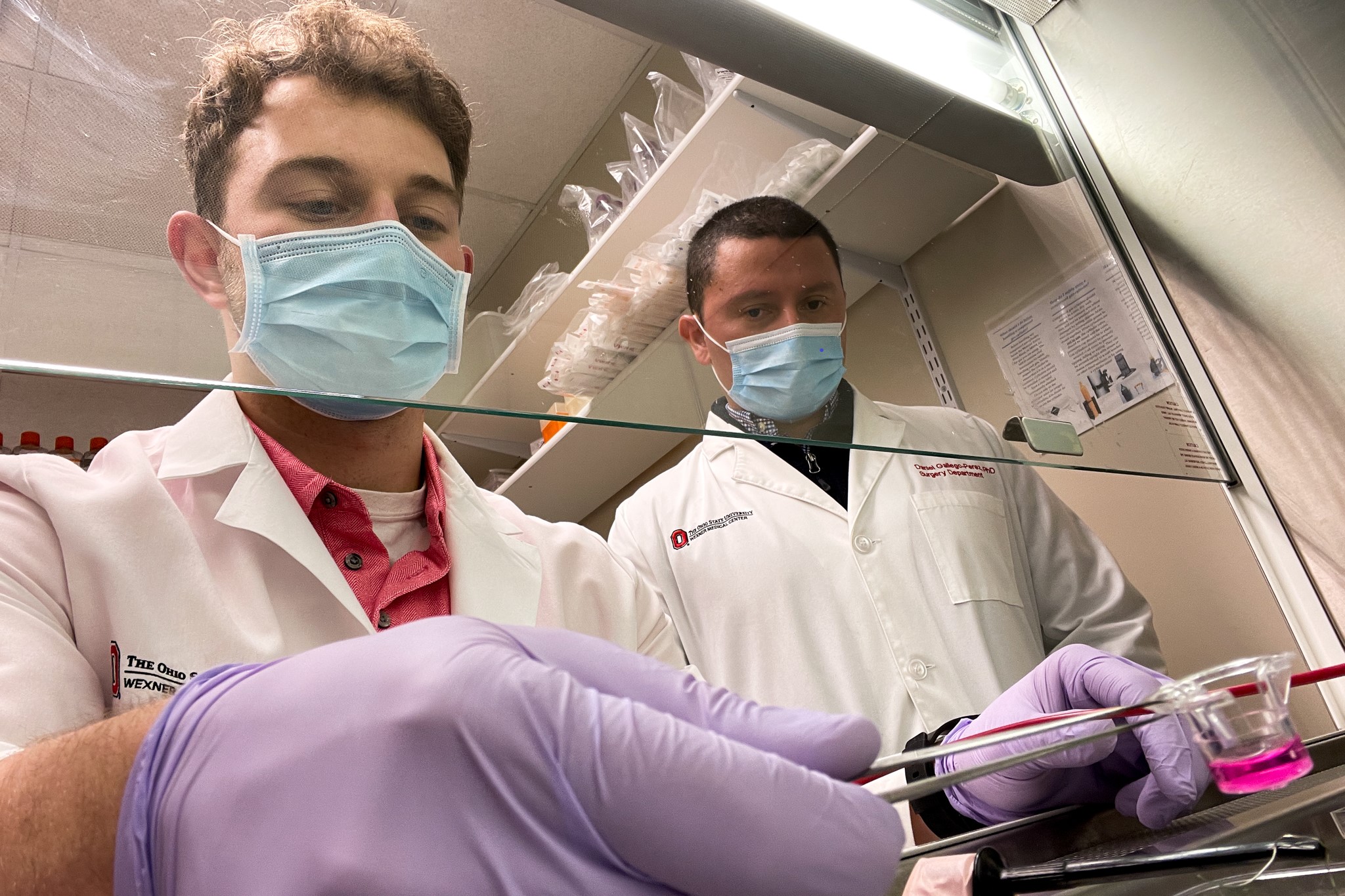

From left, researchers Luke Lemmerman and Daniel Gallego-Perez helped develop a new cell therapy that may lead to unprecedented recovery for stroke victims.

The standard of care treatment for ischemic stroke is a clot-busting drug that must be injected within hours of the first sign of symptoms. Scientists at The Ohio State University are developing an alternative: an injection of cells to promote brain tissue repair.

The research is early, and so far, tests have only been done in mice. But scientists found that the injected cells promote the growth of healthy, vascular tissue that restores blood supply. The peer-reviewed research was published Friday in the journal Science Advances.

The OSU treatment is made by taking a sample of skin cells and introducing genetic material into them. Those cells are multiplied in a lab, then injected into the test subject, said Daniel Gallego-Perez, assistant professor of biomedical engineering and surgery at OSU and leader of the research team.

“What the genes are meant to do is to instruct the cells to become blood vessels,” he told MedCity News.

The treatment was injected into the brain, but the organ was not pierced. Gallego-Perez explained that the cells were delivered on top of the cortex. After a few days, those cells spread.

According to Results in the published paper, the mice showed an increase in blood flow, compared to a control group, measured at seven, 14, and 21 days following the injection. Furthermore, the mice that received the experimental treatment regained 90% of their motor function. Improvement was also visible on brain scans, which showed signs of brain repair.

Gallego-Perez said the next step is to conduct more research to better define how the treatment is working. After that, the scientists can proceed to tests in larger animals, such as rats. More work needs to be done before the technology can be tested in patients, but the scientists have put some thought into how the treatment would translate to humans. For example, skin cells were chosen because the skin is an abundant cell source that is easy to biopsy, Gallego-Perez said. If this technology advances to human testing, the therapy could be made from a patient’s own skin cells, reducing the risk that the treatment would be rejected.

In humans, Gallego-Perez said the treatment would likely be given in a manner consistent with the way brain drugs are administered now, such as intrathecal injection. He added that his lab is exploring ways a treatment given as an injection or intravenous infusion could circulate through the body and reach the brain. The OSU team is also thinking about potential applications of the technology in other disorders that involve impaired blood flow in the brain, such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

The OSU scientists have been working on their stroke research since 2016. Their work has been funded by grants from two divisions of the National Institutes of Health: the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. Gallego-Perez said that there is still some money left to continue the animal studies, but when the research gets closer to human testing the scientists will need to consider whether to form a company or collaborate with one.

“Eventually, we will need partnerships with the private sector to get this working in humans,” Gallego-Perez said.