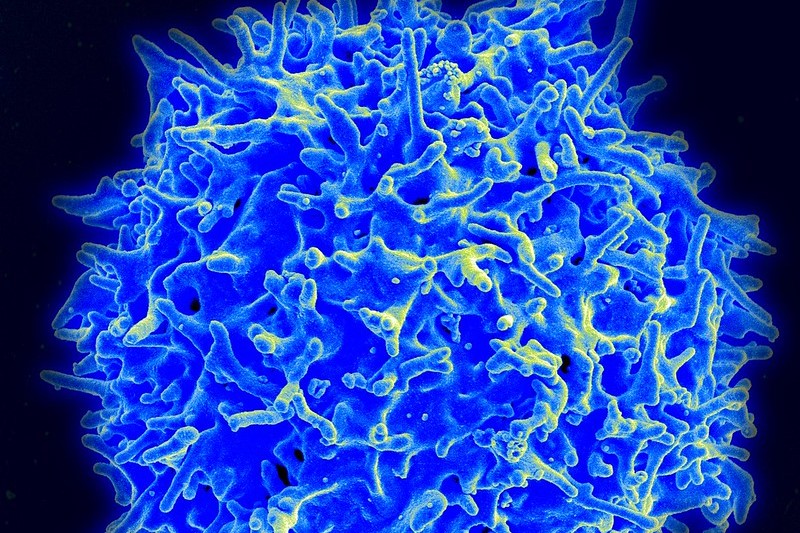

As CEO of Rubius Therapeutics, Pablo Cagnoni oversees development of a type of cell therapy made with red blood cells, but he was at Novartis when that pharmaceutical giant struck the deal for the T cell research that proved to be a beacon for the cell therapy field. That CAR T therapy offered a novel way to treat some of the toughest cases of blood cancer, but Cagnoni also acknowledged the limitations of this type of treatment.

These personalized therapies made from a patient’s own T cells are not scalable. For all of their therapeutic benefits, CAR T still poses dangerous safety risks for patients. Also, the effectiveness of this type of treatment on liquid tumors has proven elusive in solid tumors. Now, 10 years after Novartis licensed the University of Pennsylvania CAR T technology that would become Kymriah and five years since that cell therapy won a landmark FDA approval, Cagnoni says the progress he hoped the field would make has been slower than he expected.

“Those three obstacles remain, at least for CAR T cells,” Cagnoni said.

Cagnoni spoke Monday as part of a panel discussion on the potential of cell and gene therapies during the World Medical Innovation Forum in Boston. While the panelists acknowledged the challenges, they also pointed to approaches that the cell and gene therapy research is taking to overcome them.

Bristol Myers Squibb is working to improve CAR T in several different ways, said Kristen Hege, the pharma giant’s senior vice president of early clinical development, hematology/oncology & cell therapy. The company is optimizing autologous cell therapy by automating the process and improving how these cells are engineered. BMS’s development of next-generation cell therapies use gene editing techniques to knock out parts of the genome that might make a cell cause a dangerous immune response, or to knock in the properties that you would want to make it more effective as treatment, Hege said. Many of the edits for next-generation cell therapies build off of what has been learned from the first generation of CAR T treatments, she said.

Cell therapy research is going beyond T cells. Noting the encouraging early clinical data that Nktarta Therapeutics reported last week for its engineered and off-the-shelf natural killer cells, Cagnoni said that other types of cells might be able to overcome some of the challenges facing T cell-based therapies. Andrew Plump, Takeda Pharmaceutical’s president of R&D, said that his company’s cell therapy efforts are focused on innate immune cells. Takeda hasn’t done as much gene editing research as others. But Plump said that similar to BMS, Takeda’s approach is to use editing approaches to improve on some property of the cell therapy, such as ensuring delivery to the right tissue.

Cell and gene therapies are opening doors to even more complex diseases with treatments, said Catherine Stehman-Breen, CEO of Chroma Medicine. These therapies also hold the potential to address a broader patient population, she added. Her Cambridge, Massachusetts-based startup is developing epigenetic medicines that treat disease by turning genes on or off. Chroma launched last fall backed by a $125 million Series A round of funding. Stehman-Breen said that Chroma’s approach builds on the earlier work done in cell and gene therapy research.

Plump said that Takeda’s approach involves partnering with small biotechs, such as Chroma, to get access to capabilities it does not have in house. Takeda’s partnership with bispecific T cell engager developer Maverick Therapeutics led to that biotech’s acquisition last year. Plump said the deal was the product of an ongoing relationship between the companies.

Brisbane, California-based Maverick had a platform technology for making its bispecific drugs, but it did not have the capability to manufacture cell lines. Takeda provided those capabilities, leading the companies to work more closely together. The partnership, which included an equity investment, gave the pharmaceutical giant the option to acquire Maverick. Biotech company innovation in the kinds of things that Takeda does not do well in house will continue to drive the company’s investments. Offering a prediction, Plump said “we imagine that 50% of our clinical-stage pipeline in seven to 10 years will be in cell and gene therapy.”