Like many startup founders, Zack Gray’s reason for creating his company was personal. He founded Ophelia — a digital health startup that provides prescriptions to manage opioid addiction via telehealth — in 2019 after losing his girlfriend to an overdose from drugs meant to treat her accidental opioid addiction.

For a number of reasons, she had to turn to the black market to get buprenorphine and suboxone to treat her addiction. These reasons included convenience, stigma, her inability to take time off work and the fact that she was a private person. She ended up spending thousands of dollars per month on these treatments in an effort to get better. But self-treatment without guidance from a medical professional can be dangerous.

The Power of One: Redefining Healthcare with an AI-Driven Unified Platform

In a landscape where complexity has long been the norm, the power of one lies not just in unification, but in intelligence and automation.

So dangerous that she overdosed and died.

Ophelia and other telehealth companies that prescribe substance abuse recovery medications were founded so that no more patients die after self-administering life-saving drugs that were too difficult to obtain through legal means. But these companies are facing a huge blow given the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)’s proposal last month that would roll back some of the flexibilities allowed during the pandemic for the prescribing of controlled substances via telemedicine.

The rules would require an in-person exam before a prescription for drugs like narcotics and stimulants. For less addictive psychiatric medications and drugs that treat substance use disorder, patients would be able to get an initial 30-day supply via telemedicine, but would need an in-person visit afterwards.

The DEA’s proposed rules were released just months after Cerebral and other telehealth providers came under fire for taking advantage of the pandemic’s relaxed prescribing regulations. A handful of companies have been widely criticized for being too hasty and indiscriminate when prescribing addictive stimulants like Adderall to young people.

NEMT Partner Guide: Why Payers and Providers Should Choose MediDrive’s TMS

Alan Murray on improving access for medical transportation.

While the DEA touts the change as a way to ensure patient safety and prevent online overprescribing of controlled medications, several telehealth advocates argue it will greatly disrupt access for those who need the drugs — especially at a time when the mental health and substance use crisis is growing.

“One has to consider the tremendous strain that the healthcare system is under now, the fact that we have too few providers, treating too many patients, the fact that we have an ongoing substance use crisis and mental health crisis that has largely progressed relatively unaddressed because of the deficiencies in our current system with all the strain that it’s under,” said Kyle Zebley, senior vice president of public policy at the American Telemedicine Association.

The proposed rules would exacerbate the healthcare system’s ongoing challenges by throwing off patients’ continuity of care, and they would leave many patients unable to restructure their care plan, he declared. Zebley said that “the stakes couldn’t be higher.”

The permanent elimination of in-person visit requirements for telehealth controlled substance prescribing doesn’t mean that there is never any need for in-person care during the various touch points of a patient’s care journey. But when the stakes involved are considered, it is “truly life or death” for patients who have had sustained access to treatment during the pandemic, Zebley said.

What do the DEA proposed rules include?

To fully understand the DEA’s proposal, we must rewind to 2008, when the Ryan Haight Act was passed. This federal law requires an in-person visit to establish a relationship between a patient and their provider before any prescriptions can be given via telehealth.

During the early days of the pandemic, Congress waived that in-person requirement. But now that the public health emergency is set to expire on May 11, the DEA is trying to reestablish the need for in-person visits.

Under the proposed rules, all prescriptions for Schedule II drugs would require an in-person physical exam, with no allowances for short-term prescriptions. Examples of Schedule II drugs include narcotics like Percocet, Dilaudid and OxyContin, as well as stimulants like Adderall, Ritalin and Vyvanse.

For Schedule III-V drugs, patients can receive an initial 30-day prescription via telehealth. But after that, patients will need an in-person visit. This includes drugs that treat substance use disorder like buprenorphine, as well as common psychiatric drugs like Xanax, Ambien and Prozac.

The DEA is accepting the public’s comments on its proposed rules until the end of the month.

Zebley from the ATA is perplexed that the DEA’s proposal didn’t call for the creation of a special registration process. Back in 2008, Congress gave the DEA a mandate to create a process that would allow medical professionals to register with the agency and therefore be allowed to prescribe controlled substances remotely via telehealth.

“The DEA has allowed 15 years to pass, more or less, without doing anything with the will of Congress,” Zebley said. “The proposal is better than it was before the pandemic, but it’s still far more restrictive than it’s been during the pandemic. It’s a clinically inappropriate barrier to care. There’s no need for it other than a hurdle for a patient to go through.”

For instance, the proposed rules allow for an initial 30-day prescription via telehealth for Schedule III-V drugs, which was not allowed before the pandemic.

Patients have benefited from relaxed prescribing regulations for three years now. Many stakeholders advocating against the rules think the DEA is taking a significant step backwards by returning to a regulatory environment that resembles a pre-pandemic world.

Gray pointed out that the Ryan Haight Act seems outdated after the pandemic-era telehealth boom.

“The regulation was created in a very different era, in 2008. At the time, there really was no telemedicine. So the only way that the DEA could think of to interpret its patient-prescriber relationship was in-person. Fast forward 15 years — we know that telemedicine is legitimate. And yet the regulation hasn’t evolved at all to meet the new ecosystem of healthcare providers,” he declared.

What does the research show?

Mental health-related prescribing is on the rise, increasing to 21.5% of all prescriptions in 2021 from 20.1% in 2017, according to a March report from Trilliant Health, a healthcare analytics company. These prescriptions include antidepressants, anxiolytics, stimulants and antipsychotics. This increase is especially prevalent among young adults aged 18 to 44, accounting for 28% of all mental health prescriptions in 2021, compared to 20% in 2017.

Due to loosened restrictions during the Covid-19 pandemic, telehealth accounted for a larger share of stimulant prescriptions, Trilliant Health also found. In 2022, 38.4% of stimulants were prescribed via telehealth, versus 0.5% in 2017.

Some of the increase in mental health-related prescriptions can be explained by a rise in demand as Americans face unprecedented challenges from the pandemic, said Sanjula Jain, chief research officer of Trilliant Health.

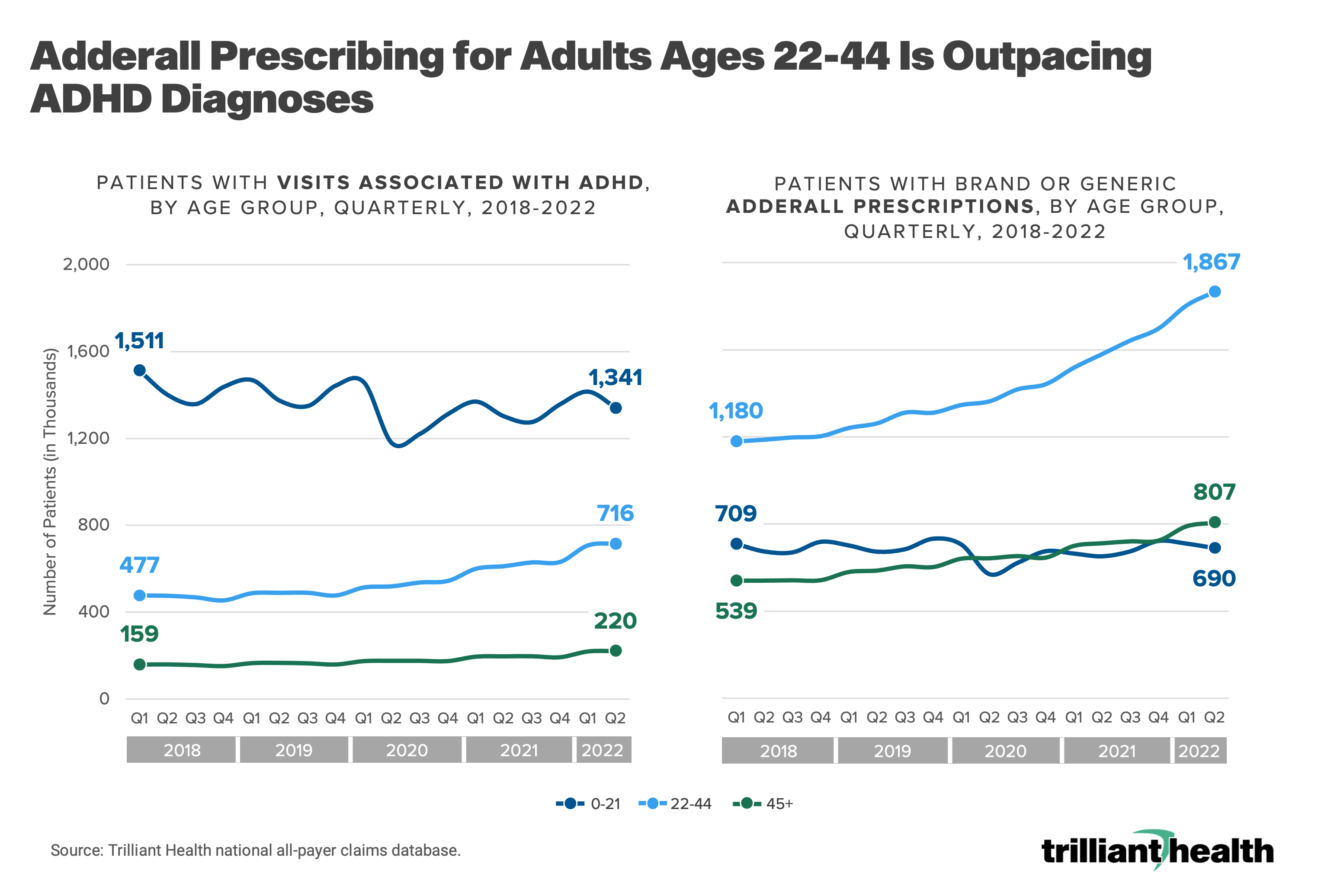

However, the research also shows instances where prescribing is outpacing diagnoses, particularly for Adderall among adults aged 22 to 44. In 2022, there were about 716,000 patients with visits associated with ADHD for this age group and about 1,867,000 patients with Adderall prescriptions. Similarly, there were 477,000 patients in this age group with visits for ADHD in 2018 and 1,180,000 Adderall prescriptions.

Although telehealth made services more accessible, the relaxed regulations created a “Pandora’s box of who is getting prescriptions,” Jain said in an interview. “With anything, you always have a handful of bad actors that could be leading to maybe some unnecessary prescribing.”

The overprescribing of stimulants is concerning due to the side effects associated with them, according to the Trilliant Health report. Those who received at least one stimulant prescription annually were more likely to have heart rate abnormalities, sleep disorders, hypertension and appetite loss or slow weight gain than those who did not receive a stimulant prescription.

Trilliant’s report does not provide data on controlled substances for treating opioid use disorder, like buprenorphine, and whether those were being overprescribed. However, another study published in JAMA Psychiatry actually showed that the pandemic-era flexibilities that were allowed for medication for opioid use disorder reduced the risk of opioid overdoses. Additionally, patients treated via telehealth were more likely to stick with treatment, according to the same study, which was conducted by researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and National Institutes of Health. This comes at a time when about 40% of counties in the U.S. are without a single provider who can prescribe buprenorphine.

What are the implications of DEA’s proposed rules?

In-person visit requirements for prescriptions given via telehealth are not supported by any major medical professional organization because there is no clinical need for them, Zebley proclaimed.

He also pointed out that prescribing is “already an extremely well-regulated area of the healthcare system” and “couldn’t be more different than the Wild West.” Prescribers must comply with other existing DEA statutes, as well as regulations set forth by the Food and Drug Administration and Federal Trade Commission. They also have to comply with state boards of medicine and other relevant boards that provide oversight over their clinical practice, he explained.

Gray from Ophelia agreed with Zebley, saying that “anyone who understands the medical aspects of care” would argue that in-person visit requirements have no clinical value.

“In fact, the DEA has offered no guidance as to what might occur at the in-person visit to prompt a doctor to discontinue the medication. There’s no purpose of the visit — it’s just a barrier,” Gray declared.

In addition to Gray, another CEO of a virtual substance use disorder provider had previously joined the chorus of opposition to DEA’s proposal.

“If these proposals end up becoming final, it will significantly decrease access to telemedicine-based opioid use disorder treatment models … I think there’s a lot of improvement that needs to be done in order to maintain access. Otherwise, it could lead to a significant increase in overdose death rates,” Ankit Gupta, CEO of Bicycle Health, said in a previous interview.

The effects can already be seen in Alabama, which instituted a new rule last year that required an in-person exam for the prescription of controlled substances. Bicycle Health flew its doctors to Alabama to perform in-person exams for its 500 patients in the state, but were only able to help about 200 to 300 patients, according to Gupta. National restrictions will only magnify these disruptions by the “tens of thousands,” Gupta previously told MedCity News.

Walmart also recently took action against the virtual prescribing of controlled substances and stopped accepting prescriptions from virtual providers unless they proved they saw the patient in person.

While there are certainly instances when telehealth prescribing of controlled substances is beneficial, the DEA rule could have some positive effects in the case of bad actors, Jain of Trilliant Health said.

“There’s a lot more research that needs to be done to really isolate which providers might be engaging in [overprescribing], what the scope is of some of those bad practices, and I think the DEA rule actually could be an important step in kind of helping manage that kind of clinical quality and kind of appropriate diagnoses before putting someone on medication,” she stated.

But Zebley argued these negative media reports are no reason to restrict patients’ access to life-saving medicines.

“I would make clear to the DEA and others that these news stories are emblematic of issues that one has in the healthcare system generally, not exclusive to virtual care. There are obviously mistakes that are made in-person as well. Just because there are a few of these stories does not mean that you erect barriers that are going to be extraordinarily problematic to a really sensitive, vulnerable, underinsured population who will potentially be left out on their own,” he declared.

And Gray said he doesn’t even believe DEA’s changes are even tenable or enforceable.

The proposed rules put providers in an incredibly tough and unclear moral dilemma because they’re allowed to start a patient with treatment, but must completely cut them off if they fail to see a provider in-person within the next 30 days, he explained.

“But we know that opioid overdose is taking the lives of 200 people every day. It’s the number one cause of death for Americans under 50. And if you’re a well-intentioned provider and you have a patient who suddenly can’t fill the prescription, well, there’s a very good chance they’re gonna go out and use drugs again and possibly die,” Gray said.

If a patient is unable to meet the in-person visit requirement in 30 days, providers will be faced with the difficult choice of breaking the law or risking their patient’s life, he pointed out.

It’s easy for regulators to forget how many barriers to care exist in the U.S. healthcare system, and how many patients try their best to take part in an in-person visit but still can’t, Gray explained. This is especially true for patients on Medicaid, which is Ophelia’s main patient population. Many Medicaid clinics are backed up for weeks, and many Medicaid patients work multiple jobs and are at the whim of their bosses’ schedules. So it’s plain to see how someone might miss an appointment or be unable to receive in-person care during such a short window, he said.

Only time will tell which side will prevail in the debate over whether a few rotten provider apples spoil the entire telemedicine-prescribing barrel when it comes to managing our opioid crisis. The DEA is expected to finalize the rule after the public comment period comes to a close at the end of the month.

Photo: Motortion, Getty Images