One of the hottest debates in biotech today involves cell therapy. Autologus cell therapies—treatments made by engineering a patient’s own immune cells—established the field. But making such treatments from donor cells offers the promise of a less expensive and more scalable approach that could enable these allogeneic cell therapies to displace autologous ones.

The changing of the cell therapy guard is no foregone conclusion. Allogeneic cell therapies have had clinical trial setbacks, and the data on whether they can be as effective and long-lasting as autologous therapies has not been encouraging so far. Persistence and durability of these therapies is crucial because these measures shape how the therapy is valued by investors and payers—if they reach the market.

With the Rise of AI, What IP Disputes in Healthcare Are Likely to Emerge?

Munck Wilson Mandala Partner Greg Howison shared his perspective on some of the legal ramifications around AI, IP, connected devices and the data they generate, in response to emailed questions.

“Until you have more robust data in terms of persistence and durability, you are not going to get the investment enthusiasm,” said Chris Learn, vice president of cell and gene therapy at Parexel, a contract research organization.

Learn spoke during a cell and gene therapy panel discussion this week at the Biopharm America conference, held this year in Raleigh, North Carolina. He was joined by Shailesh Maingi, CEO of consultancy and investment firm Kineticos Life Sciences, and Matthias Schroff, CEO of cell therapy startup Inceptor Bio.

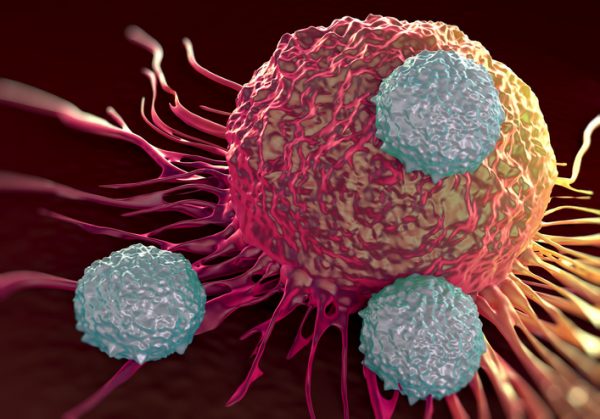

Schroff said his company started by “working backwards,” trying to determine how its product would fit in the market. That way, Inceptor could figure out how to make it could stand out. Whereas CAR T-therapies are made by engineering a patient’s T cells, Morrisville, North Carolina-based Inceptor develops its therapies by working with two other types of immune cells, monocytes and macrophages. Those cells are engineered to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) that enables them to identify and attack cancer cells. Inceptor licensed this CAR-M technology from the University of California Santa Barbara.

One of Inceptor’s goals is using cell therapy to treat solid tumors, which have eluded CAR T-therapies. A smaller company must have the discipline to prioritize. Schroff noted that Inceptor’s platform technology offers the potential to address many targets. But for the financial viability of the company, it has honed its focus.

“The major value inflection point is clinical data, so you have to focus on one indication, one target,” Schroff said.

Maingi, who was Inceptor’s founding CEO and is now the startup’s executive chairman, said biotech companies should pay close attention to what has been funded as well as what has not received funding. He cautioned that certain disease targets are on the “do not fund” list for investors, though that list will vary from firm to firm. For Kineticos, top of the do not fund list is anything addressing the cancer protein CD19. It’s a crowded space with too many active clinical trials underway for that target, Maingi explained.

Allogeneic cell therapy is another area where Kineticos is steering clear. Maingi said there are no good data yet showing durability of these off-the-shelf cell therapies. He wasn’t always so skeptical. But he said the promise that one batch of donor cells could yield therapies for 1,000 patients was whittled down to hundreds, then tens, then single digits. Along the way, the number of edits made to those cells went up. Now some companies are making 10 or more edits to cells to make allogeneic cell therapies. Maingi said that with so many edits, it’s unclear what kind of therapeutic function will be left.

“I don’ think [allogeneic cell therapy] will get abandoned, but VCs like me will see the next shiny thing, which is in vivo,” he said.

Biotech research is underway to make cell therapies by editing cells in vivo—inside the patient. If in vivo cell therapies catch on, allogeneic cell therapy may never catch up, Maingi said. Schroff sees room for both autologous and allogeneic cell therapies. But he noted that his company’s technology requires an autologous approach. Inceptor’s CAR-M therapies are autologous because an allogeneic CAR-M would not have the same function, he said. Schroff added that while in vivo cell therapy sounds exciting, developing it may present more challenges than allogeneic cell therapies.

Learn noted that the cell therapy field already has an allogeneic cell therapy. Late last year, the European Medicines Agency approved Ebvallo, an allogeneic Atara Biotherapeutics cell therapy for treating Epstein-Barr virus positive post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease. In certain indications, there may be opportunities for allogeneic cell therapy, he said.

Meanwhile, the current lineup of FDA-approved autologous cell therapies is finding wider adoption. These therapies will continue to grow by moving into earlier lines of therapy, Learn said. Cell therapy initially reached the market for patients who had exhausted other treatment options. Learn said in earlier lines of therapy, they will be even better because the patients aren’t as sick so they will be more amenable to a cell therapy. Moving these therapies into earlier lines of treatment will require new payment models, perhaps tying the payment of these medicines to their performance or durability, Maingi said. He added that the healthcare industry will find ways to pay for these therapies because they extend the lives of patients who otherwise would die.

“We’re going to find a way to pay for them,” Maingi said. “It’s not going to be what we’re doing right now but we will find a way.”

Image: royaltystockphoto, Getty Images