Gene therapy is now here for patients with sickle cell disease. The FDA on Friday approved treatments from Vertex Pharmaceuticals and Bluebird Bio, each offering a potentially curative treatment for the inherited blood disorder.

Approval for Vertex’s Casgevy came right on the target date for an FDA decision and three weeks after regulators in the United Kingdom made the treatment the first approved CRISPR-based therapy in the world. For Bluebird’s treatment, named Lyfgenia, the approval comes nearly two weeks early. The FDA decisions for both therapies cover patients age 12 and older.

“Sickle cell disease is a rare, debilitating and life-threatening blood disorder with significant unmet need, and we are excited to advance the field especially for individuals whose lives have been severely disrupted by the disease by approving two cell-based gene therapies today,” Nicole Verdun, director of the Office of Therapeutic Products within the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in the agency’s approval announcement. “Gene therapy holds the promise of delivering more targeted and effective treatments, especially for individuals with rare diseases where the current treatment options are limited.”

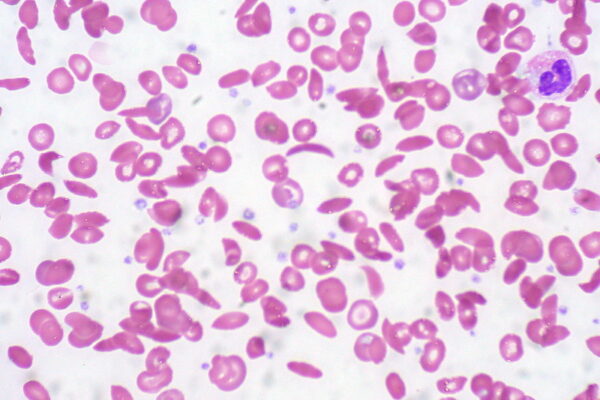

Sickle cell disease stems from mutations in the oxygen-carrying protein hemoglobin in red blood cells. Healthy red blood cells are round and flexible. Patients who have sickle cell disease develop red blood cells that are rigid and shaped like crescents or sickles. These sickled cells block blood flow, depriving tissue of oxygen in what’s known as a vaso-occlusive crisis. This complication can cause painful episodes that require hospitalization. Recurrence of this complication can lead to disability and an early death. A bone marrow transplant is a treatment option, but this procedure requires a matched donor and comes with the risk of rejection.

Both Casgevy and Lyfgenia are made by harvesting stem cells from the patient’s bone marrow. Those cells are then modified in the lab. The therapy of Boston-based Vertex employs CRISPR to edit a gene in the cells to produce high levels of fetal hemoglobin. The therapy of Bluebird, based in Somerville, Massachusetts, uses an engineered lentivirus to modify cells to produce a version of hemoglobin that functions similarly to hemoglobin produced by adults who do not have sickle cell disease. Both therapies are administered to patients as one-time infusions.

The approvals of Casgevy and Lyfgenia are based on clinical trial data showing reductions in vaso-occlusive crises. The main goal of the Vertex therapy was to show freedom from severe episodes for at least 12 consecutive months during a 24-month follow-up period. Results showed 93.5% of the 31 evaluable patients met this mark. For Lyfgenia’s pivotal study, the main goal was to measure resolution of vaso-occlusive crises between six and 18 months after infusion of the therapy. Study results showed 88% of the 32 treated patients achieved this goal.

The Power of One: Redefining Healthcare with an AI-Driven Unified Platform

In a landscape where complexity has long been the norm, the power of one lies not just in unification, but in intelligence and automation.

Unlike Vertex’s Casgevy, the Lyfgenia label has a black-box warning that notes cases of blood cancer have occurred in patients treated with this Bluebird therapy. The label cautions clinicians to monitor patients for signs of cancer. Last week, the FDA disclosed it is investigating cases of cancer that followed treatment with cancer cell therapies. Such secondary cancers are known risks of cell and gene therapies that employ a viral vector to introduce genetic material. In 2021, a reports of cancer temporarily halted clinical development of an earlier version of the Bluebird sickle cell disease therapy, then known as LentiGlobin. The company was later cleared to resume clinical testing after an analysis concluded the cancer diagnosis was not likely related to the gene therapy. The FDA said that patients who receive both sickle cell gene therapies will be followed in long-term studies to further evaluate safety and efficacy.

Vertex set a wholesale price of $2.2 million for Casgevy. Bluebird’s Lyfgenia is more expensive at $3.1 million, which the company said recognizes the value that the therapy may offer over time by reducing or even eliminating the severe complications that sickle cell patients experience. Bluebird will offer payers the option of choosing outcomes-based agreements that tie reimbursement of the drug to its achievement of clinical benefit measured over three years. Bluebird has experience with these agreements, having implemented a similar one for Zynteglo, a gene therapy approved last year for the treatment of a different rare blood disorder called beta thalassemia. Zynteglo’s price tag is $2.8 million.

In a note sent to investors Friday, William Blair analyst Sami Corwin said Lyfgenia’s black box warning and higher price pose commercialization challenges for the Bluebird therapy. Leerink Partners analyst Mani Faroohar wrote in a research note that both approvals are in line with expectations, but Bluebird is further disadvantaged by not receiving a priority review voucher, a voucher that enables faster FDA review of another rare disease product. Companies can receive these vouchers for developing new treatments for rare diseases, and they are often sold at prices topping $100 million. With no voucher to sell, Bluebird will be unable to effectively commercialize the new product, Foroohar said.

Vertex is also seeking FDA approval of Casgevy in beta thalassemia. A regulatory decision in that indication is expected in March. The William Blair analysts said Casgevy’s approval in sickle cell disease makes a beta thalassemia approval more likely.

Photo by Flickr user Ed Uthman via a Creative Commons license