Autoimmune disease is an unrelenting attack of the body on itself. Drugs that suppress the immune system quell the attack for a while, but patients need to keep taking these medicines, putting them at risk for complications that come from a chronically suppressed immune system.

What if a patient could just start over with immune cells that don’t target bodily tissue? Ouro Medicine aims to achieve that with a drug candidate that works like an immune system reset button. This program is on track to enter the clinic and the startup has more in the pipeline. On Friday, San Francisco-based Ouro emerged from stealth revealing $120 million in funding from backers that include GSK, which helped form the young company.

“Fundamentally, we think this could change the practice of medicine if we’re right,” CEO Jaideep Dudani said. “The way these patients are treated currently, they’re always taking drug. We (believe we) can put them into durable remission without chronic immunosuppression.”

The Power of One: Redefining Healthcare with an AI-Driven Unified Platform

In a landscape where complexity has long been the norm, the power of one lies not just in unification, but in intelligence and automation.

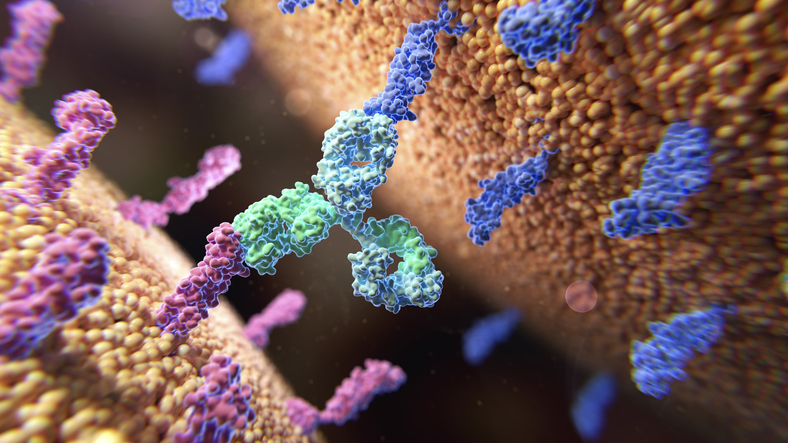

Ouro’s drugs are part of a class of therapies called T cell engagers, or TCEs. By simultaneously binding to a T cell and a disease-driving cell, these engineered antibodies direct the T cell to kill the pathogenic cell. TCEs first reached patients as cancer treatments. But dysregulated cells that drive certain cancers are also behind certain autoimmune diseases. Research is underway at multiple companies aiming to expand the scope of cancer immunotherapy to autoimmune disease.

Ouro was founded by Monograph Capital. Dudani, who is also portfolio principal at Monograph, said the venture capital firm had been tracking the immunology space, watching the data for CAR T-therapies as this class of medicines expands from cancer to autoimmune disease. Monograph also started working with GSK to form the immune reset company that would become Ouro. GSK has a longstanding history in B-cell biology, Dudani explained. The company’s portfolio includes Benlysta, a lupus drug that works by blocking an enzyme B cells need to survive.

Two studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine in September turned Ouro on to TCEs. Both studies were tests of Tecvayli, a Johnson & Johnson TCE already approved as a treatment for multiple myeloma. This drug targets BCMA, a protein abundant on the surface of the B cells that drive this blood cancer. B cells also drive certain immune diseases, such as lupus, scleroderma, and rheumatoid arthritis. In the test of Tecvayli in four patients with severe autoimmune disease, results showed a reduction in autoantibodies as well as a clinical response. The other study evaluated Tecvayli in a woman whose aggressive lupus did not respond to other treatments. After a short course of Tecvayli, she had a drug-free complete remission.

The sample size of these studies is small, but Dudani characterized the results as “remarkable clinical data.” Ouro found its own candidate in China, licensing OM336, a TCE that Keymed Biosciences is developing for multiple myeloma. After securing exclusive rights to the drug outside of greater China, Ouro closed the Series A round of funding in November, Dudani said.

NEMT Partner Guide: Why Payers and Providers Should Choose MediDrive’s TMS

Alan Murray on improving access for medical transportation.

TCEs for cancer come with warnings for the risk of severe side effects, but Dudani expects the safety profile in immunological indications will be better. The lower disease burden of autoimmune disease compared to cancer permits lower doses and shorter courses of therapy, which reduces the risk of adverse effects. He also expects the drugs will have a longer-lasting effect. Depleting disease-driving cells erases the memory that these cells targeted the body. The naïve cells that repopulate the immune system are not exposed to a self-antigen that makes them pathogenic, so these new cells could enable long periods of remission.

“You’re not repopulating with cells that are autoreactive, you’ve reset the body to not be as reactive to self,” Dudani said. “So the hope is when these cells repopulate, they come back in a more naïve fashion to be less self-toxic.”

Interest in bringing dual-targeting antibodies to autoimmune disease is growing. In October, GSK acquired global rights to a TCE from Chimagen, which the pharma giant plans to advance to Phase 1 testing in lupus this year. Candid Therapeutics’ $370 million in funding and two in-licensed TCEs were unveiled days after the September publication of the Tecvayli data. Before that, Merck licensed rights to a bispecific antibody with plans to develop it in cancer and autoimmune disease. And Cullinan Therapeutics last year changed its name from Cullinan Oncology to reflect the expansion of its TCE research to autoimmune disease.

Despite the progress of the TCE field, there are stumbles. On Thursday, IGM Biosciences announced it would stop work on two TCEs and restructure its operations after an interim look at clinical data showed lower than expected B cell depletion.

Ouro’s Series A round was co-led by TPG Life Sciences Innovations, NEA, and Norwest Venture Partners. Other disclosed investors in the financing include Monograph Capital, GSK, Boyu/Zoo Capital, LongRiver Investments, and UPMC Enterprises. With the funding, Dudani expects Ouro can begin a Phase 1 test of OM336 later this year.

The rest of the pipeline consists of discovery-stage assets internally developed by Ouro. All of them target different aspects of B-cell biology to achieve an immune system reset, Dudani said. That aspiration led to the name of the company, which refers to the ouroboros, a circular symbol of a snake devouring itself.

“It represents eternal rebirth and recycle,” Dudani said, adding that Ouro’s drugs “give the opportunity for immune reset and rebirth.”

Illustration: Thom Leach/Science Photo Library, via Getty Images