Genetic medicines R&D is making strides with more complex DNA molecules. While these long sequences of synthetic DNA are key for developing gene and cell therapies as well as antibodies and other biologic drugs, their length also poses a problem. The prevailing way of synthesizing DNA is a decades-old process employing harsh chemicals that damage the DNA strands as they are made. The longer you go, the more damage occurs, said Daniel Lin-Arlow, co-founder and CEO of Ansa Biotechnologies.

“The chemical method got us all the miracles of biotechnology we have today, I have a lot of respect for that,” Lin-Arlow said. “But nature can make very long molecules without damaging them.”

Ansa’s DNA synthesis technology uses enzymes. This approach enables the making of long, complex sequences without damaging them, Lin-Arlow said. Emeryville, California-based Ansa has been developing this technology for the past four years. The startup is now preparing to show potential customers what enzymatic synthesis offers and it has raised $68 million to scale up operations and launch its offering.

The Series A round of funding announced Monday was led by Northpond Ventures.

While chemical synthesis has been around since the 1960s, enzymatic synthesis is even older. The key enzyme, terminal deoxynucleotidal transferase (TdT), was first discovered in 1959, Lin-Arlow said. The challenge with using this enzyme is controlling it—adding one base to the sequence and then getting the enzyme to stop. TdT can be controlled with a “reversible terminator,” a nucleotide that blocks the addition of additional bases to the sequence. But Lin-Arlow said that this approach is challenging because TdT doesn’t like to accept nucleotides with these kinds of blocking groups.

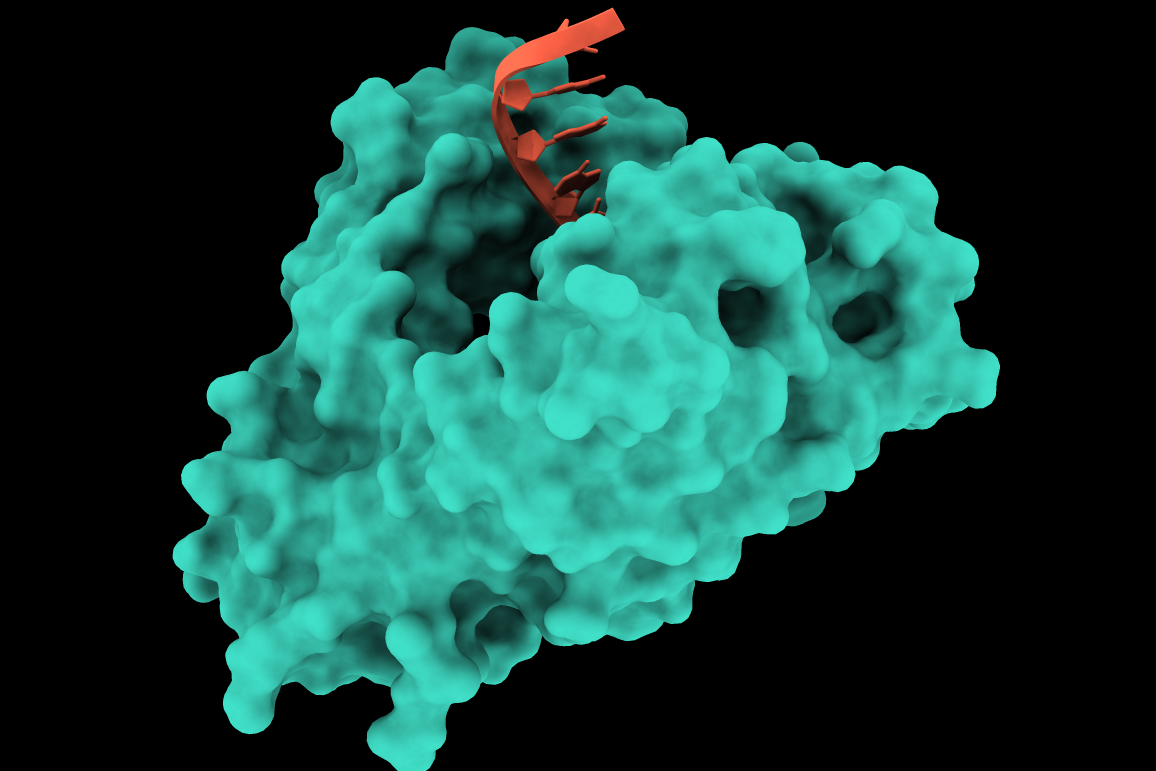

Ansa developed a way to control TdT without a reversible terminator. The company’s technology takes the TdT enzyme and tethers a nucleotide to it using a linker. Because the enzyme has only one nucleotide, it can add only one. After adding that nucleotide, the enzyme stops, preventing other conjugates from adding their molecules. To extend the sequence further, the linker is cleaved to release the TdT enzyme, enabling the process to repeat.

“You want to get the enzyme to add exactly one base, not zero and not two,” Lin-Arlow said. “It’s also essential that [the enzyme does] not damage the DNA.”

Ansa’s technology stems from the graduate research of Lin-Arlow and company co-founder Sebastian Palluk at the University of California at Berkeley. In 2018, they were both among the authors of a paper published in Nature Biotechnology describing this enzymatic approach.

Lin-Arlow said he has been talking with potential customers about piloting the Ansa technology, serving as a service provider to these research-stage companies and building for them the sequences that they struggle to get from other vendors. In addition to the biopharmaceutical sector, Lin-Arlow said potential users of the technology include industrial biotechnology companies that are using synthetic biology to engineer microbes to produce chemicals. The company is already working with Microsoft in a collaboration developing enzymatic reagents that can be used for DNA-based storage. The idea is to store digital information in the sequences of DNA molecules as a way of archiving information.

“One big advantage of that is DNA, stored under the right conditions, could be stored for thousands of years,” Lin-Arlow said. But Ansa’s “focus in the near term is pharma and other synthetic biology applications.”

Though chemical DNA synthesis has been around for decades, it has seen some innovations. The technology platform of Twist Bioscience “writes” DNA on a silicon chip, an approach that miniaturizes the process and brings precision, automation, and scalability to the chemical method of DNA synthesis. In the fiscal year ending Sept. 30, 2021, Twist reported $132.3 million in sales of synthetic DNA products, a nearly 47% increase over the prior fiscal year.

In enzymatic synthesis, Ansa will compete against other startups that have also been raising money. DNA Script’s contribution to enzymatic synthesis is a benchtop instrument that labs can use to print synthetic nucleic acids on demand. In January, the France-based company closed the second tranche of its $200 million Series C round of funding. San Diego-based Molecular Assemblies is advancing its enzymatic technology toward commercialization and it closed a $25.8 million Series B round last month to support that push.

Lin-Arlow contends that Ansa’s approach is better than other enzymatic synthesis technologies. Competitors still use chemistry for the blocking step that stops the TdT enzyme, he said. Ansa’s process is entirely based on enzymes, using a different enzyme to stop the process. The Ansa approach should also be less expensive, Lin-Arlow said. While raw materials of chemicals can be less expensive than enzymes, the savings will come from streamlining the manufacturing process, he explained.

Lin-Arlow said Ansa raised pre-seed financing at the end of 2018, the same year the startup’s research was first published. The company closed $9.2 million in 2020, a sum that represents both the pre-seed and seed funding. Including the Series A round, Ansa says it has raised a total of $82 million to date. Other participants in the latest round of funding include new investors RA Capital Management, Blue Water Life Science Advisors, Altitude Life Science Advisors, Fiscus Ventures, PEAK6 Strategic Capital, Carbon Silicon, Codon Capital. They were joined by earlier investors Mubadala Capital, Humboldt Fund, Fifty Years, and Horizons Ventures.

Image by Ansa Biotechnologies