One of the things that makes successful serial entrepreneurs so inspiring is that even when they fail, they evaluate where they went wrong, begin again and learn from their mistakes. Frequently they share that knowledge with others. Anyone looking for confirmation of that should take a look at the wealth of insights in CB Insights collection of 51 startup post mortems (we did a shorter version based on the post).

There are even some investors in that group, namely Bruce Booth, an Atlas Venture partner focused on emerging biotech therapeutics companies and author of the blog LifeSci VC. As he hastens to remind readers in the post, not every deal is a winner. He shared the experience of a poor investment in healthcare, specifically in a cancer diagnostics firm Q-ity, and why it didn’t work out.

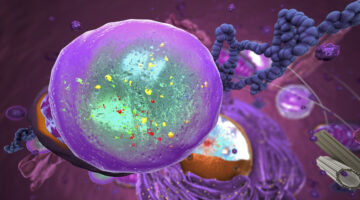

It was one of four investors in a $26 million Series A round in 2009. From Booth’s perspective, the company had several strong points in its favor. It appeared to have a game-changing technology involving cancer and personalized diagnostics and circulating tumor cells, a team with decent experience in the diagnostics market, strong IP, good valuation and several different exit options, either through an M&A by a diagnostics or oncology company or a possible IPO.

HealthBook+ CEO Shares Vision for How People Can Own Their Health by Leveraging Data and AI

HealthBook+ provides a way for individuals to aggregate and use their personal health information safely and securely to power AI engines that direct people to their next best health action. Importantly, it also gives employers predictive insights to help them provide the most relevant benefits for their employees.

In retrospect, it’s not like Booth didn’t see potential risks with the investment. They just were not as magnified as they should have been, he writes.

One of the biggest issues was the baggage of the company — it was the product of a merger, which led to a rocky integration.

It also proved to be an instructive reminder on deal structure.

“If a technology can be validated on a smaller financing, it should be. It gets back to our mantra at Atlas of Prove-Build-Scale. Instead of raising a ‘Build-stage’ $26 million Series A without any tranche or milestone points, we should have broken up the capital to prove the story first. Sadly, we knew within months that the DNA Repair story was going to be an uphill battle. I remember the late 1Q 2010 board meeting well: the initial trial data were far from clear, but clearly far from what we had all hoped for.”

BioLabs Pegasus Park Cultivates Life Science Ecosystem

Gabby Everett, the site director for BioLabs Pegasus Park, offered a tour of the space and shared some examples of why early-stage life science companies should choose North Texas.

Booth’s post also offers some valuable perspectives on the downside of personalized medicine and diagnostics, from an investment perspective.

“Diagnostics aren’t for the faint of heart and are a much tougher place to make returns today than other life science subsectors. Despite the frothy commentary about personalized medicine and the dawn of diagnostics, it’s a very tough business that faces many of the risks and costs of drug R&D but without the upside.”

It also “needs to get to commercialization before a material exit outcome.”

It would be great if more investors had the courage to share investment mistakes they have made. It only adds to the understanding of the complexities behind life science investments and to the appreciation of the relatively few deals that succeed.