Can Covid-19 kill healthcare as we know it? The answer is yes.

Whether that is good, or bad, or just the reality we need to face, depends on your perspective.

First, let’s discuss the good. For years, tech entrepreneurs, healthcare innovators and supporters of “innovative disruption” have urged slow-moving health systems and the provider community to adopt digital tools. Their exhortations are finally having an impact.

Telemedicine use has skyrocketed. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has rightly loosened regulatory requirements including allowing virtual visits to occur through FaceTime or Skype. This is a boon for the millions who are sheltering in place as well as for clinicians and doctors who have to take care of patients. Not surprisingly, this has been fortuitous for companies that are providing the digital tools to create such encounters.

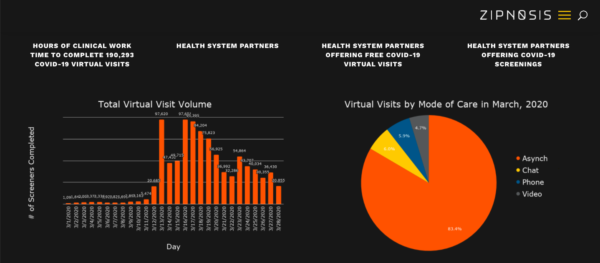

My inbox is overflowing with startups offering virtual care, triage, screening, chatbot-related offerings and then some. All are keen to help tame the Covid-19 beast. Consider this graphic of telemedicine use below from just one provider of virtual care – Minneapolis-based Zipnosis. Click to enlarge.

A Deep-dive Into Specialty Pharma

A specialty drug is a class of prescription medications used to treat complex, chronic or rare medical conditions. Although this classification was originally intended to define the treatment of rare, also termed “orphan” diseases, affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US, more recently, specialty drugs have emerged as the cornerstone of treatment for chronic and complex diseases such as cancer, autoimmune conditions, diabetes, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS.

“Once patients get used to telemedicine…I think it changes the whole business model.”

Now, let’s look at what this dynamic may create down the road for health systems when we emerge from Covid-19’s collective nightmare. Here’s how Kevin Schulman, professor of medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine and professor of economics at the institution’s Graduate School of Business, describes it:

Once patients get used to telemedicine, are they going to come back to the idea of coming into the clinic, waiting in long queues for really low-quality service from a convenience perspective? And that’s going to potentially have even a longer-term impact on the healthcare system. This could be the thing that pushes the system to a different way of delivering care.

I think it changes the business model. I think it makes it much more complicated. So if you are doing telemedicine services, you are potentially opening up to lots of different kinds of competition. You have huge issues of coordination of care. You have huge issues about how you are going to invest in this new business line and staff the new business line.

And what are you going to do with all the new buildings you just built? So that would be interesting. Healthcare runs in such high fixed costs and high capacity that even small changes in demand will have big, potential impact on the economics.

Independent physician practices will dwindle

That economic impact is being felt almost immediately by independent physician’s practices who have ramped up the use of telemedicine. Consider a joint letter sent to Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar and CMS Administrator Seema Verma, by 17 primary care groups and software companies aiding providers. They include the likes of Farshad Mostashari, CEO of Aledade and Rushika Fernandopulle, co-founder and CEO of Iora Health. The letter states that in recent days more than 90 percent of visits have become virtual for some of the signatories. They lauded recent CMS policy changes to remove barriers to adopting but urged Azar and Verma to consider immediate reimbursement improvements for remote care for Medicare beneficiaries. Specifically, they are asking the following:

- Telehealth eligibility for risk adjustment: Allowing all forms of telehealth (including audio only phone encounters) to be eligible for disease burden capture for risk adjustment in CMS programs (e.g., the identification and (re)confirmation of hierarchical condition codes (HCCs) within Medicare Advantage (MA) or Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) during the period of the pandemic.

- Telehealth reimbursement: Leveling the playing field for providers seeking telehealth reimbursement to be “made whole” when providing telehealth services rather than inperson care.

The letter states that though CMS’s press release dated March 17 indicated that telehealth services will be paid under the Physician Fee Schedule in the same amount as in-person care, under Medicare’s current reimbursement methodology “that does not hold true.” That’s because according to the letter, Medicare Telehealth Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) also dated March 17 states that “telehealth encounters are to be paid at the ‘facility’ payment rate differential inherent in the use of Place of Service (POS) code 02 (telehealth) for telehealth claims” that roughly translates to a reduction of 31 percent. The letter goes on to say:

We are not designed with the lower cost structure of a virtualized service established to only provide telehealth or other remote approaches Even though the policy to approve telehealth is a strong step forward, the reduction in payment of approximately 30%1 will have a significant impact to the viability of most medical practices that still rely on visits as a revenue source.

A healthcare industry expert went further on the viability issue facing independent physician groups.

“They are a very much like small business, so if you take away half their revenue because people won’t come in, they don’t have the balance sheet to survive the way a big system can survive,” said Sanjay Saxena, senior partner and managing director with Boston Consulting Group, in a phone interview last week. “Independent physician practices that are out there are going to see the need to tie up with or become part of the big [health] systems. And that trend was already going on but the financial pressures related to Covid will do that as well.”

Hospital have-nots will have some tough decisions to make

The impact on health systems and standalone hospitals will also depend to some extent on the strength of their balance sheets. In the short term, many hospitals across the country have voluntarily canceled and/postponed elective procedures to reduce the chance of spreading the novel coronavirus.

But this has immediate ramifications for their bottom line given that many hospitals have thin margins as it is and removing the most profitable procedures – like joint replacements – will feel like a gut punch. It would be one thing if all hospitals were like academic medical centers who would be able to take the financial hit from canceled procedures because they are also going to get reimbursed for treating Covid-19 patients.

“If you are an academic medical center — like a Stanford or UCSF out here in the Bay Area — you are seeing very high degrees of utilization and so the revenue side is there,” Saxena added. “Yes, you have some things you have to offset but you have some of the revenue benefits that come with the Covid volume.”

But what if you added capacity in preparation for a surge that does not come. Then, a ban on elected procedures can be very costly.

“If you are a community hospital and you are not getting that, and you already don’t have a strong cash position, because your daily cash on hand is not that as high and you haven’t been running at high occupancy, then the notion of having your hospital idle your elected procedures puts you in a different financial position than [some other hospitals] who are going to lose something but they won’t be as great,” Saxena said. “And they have a balance sheet and daily cash on hand to weather that.”

Saxena described hospitals with 100-200 beds in rural areas as the ones most vulnerable because in many cases they don’t have large volumes and strong cash on hand to begin with.

But what about the $100 billion in stimulus money that has been reserved for hospitals? Wouldn’t that help them from failing?

“If we come out of this and it’s a two three month period, it’s one thing but if Covid goes on for a long period and hospitals have to make fundamental shifts in how they take care of people then obviously the need will grow past that.”

And the longer it goes, there is a chance that the wave of consolidation in the healthcare industry continues and maybe even accelerates with larger health systems buying up the ones with weak balance sheets.

“A prolonged pandemic threatens the way we finance healthcare”

A Republican-controlled Senate passed a stimulus bill designed to rescue Americans from the economic fallout of Covid-19 and perhaps it’s a sign of things to come. Don’t be surprised if you see a profound psychological shift around questions of access to basic care and how to pay for it. In fact, there may be a greater appetite in the country to assume that the government will assume more of the risk of providing healthcare coverage.

A health plan executive who requested anonymity to speak openly about things he is musing on implied that Covid-19 would essentially require people to question fundamental assumptions about who pays for what.

“A prolonged epidemic, I think, threatens our whole system of financing healthcare and you could imagine a different approach to healthcare financing that comes out of this,” he said.

He wouldn’t comment any further when pressed on whether the way forward is Medicare for All but the implications of his words, at least to me, are clear. The system that we have today for paying for care is woefully inadequate. Everyone already agrees philosophically — and if they didn’t, they likely do now — that every American should have a right to care without worrying about how they are going to pay for it. And we have already achieved this in our current crisis. Whether by government mandate or voluntarily, many payers have already waived cost-sharing so that people are insulated against any monetary burden should they contract Covid-19.

This raises an important question. Why can’t we do it for everything?

A for-profit insurance system cannot take on the massive risk that this approach will involve and survive as a successful business entity. The only answer is that the government must step in. But single-payer, Medicare For All solutions are anathema to many, and such programs will undoubtedly cause hardship to people who are working in the insurance industry. Could Medicare Advantage be expanded to cover all Americans? Could we follow Israel’s example?

Where we go and how swiftly we get there, of course, depends on the outcome of our presidential elections. But it’s safe to say that the healthcare industry — with or without major policy changes at the federal level — is as much a casualty of Covid-19 as the scores of people that have fallen victim to the pandemic.