Recently, President Joe Biden announced a new federal goal of reducing the cancer death rate by at least 50% over the next 25 years. It’s an audacious goal, and one that I applaud.

According to the CDC, over the past 20 years, cancer death rates have gone down 27%, from 196.5 to 144.1 deaths per 100,000 population. That’s the good news. Now the bad: In 2022, you are no more likely to survive five years with an advanced solid cancer like pancreas or lung cancer than you were when my 1955 model 41D Buick Special rolled off the assembly line in Detroit.

Behavioral Health, Interoperability and eConsent: Meeting the Demands of CMS Final Rule Compliance

In a webinar on April 16 at 1pm ET, Aneesh Chopra will moderate a discussion with executives from DocuSign, Velatura, and behavioral health providers on eConsent, health information exchange and compliance with the CMS Final Rule on interoperability.

Despite that sobering update on where we really are, I was very encouraged by a few of President Biden’s comments. His administration has rightfully targeted the real potential of combining existing drugs for more effective cancer treatments. This has been underutilized, but has great potential if correctly applied.

As Biden noted, we need to be able to determine which treatment combinations work best for a particular person. As it stands, Biden said, we know far too little about why a treatment works in some patients and not in others with the same exact diagnosed cancer.

The president’s realizations are laudable and dovetail nicely with the successes we’ve had using human tumor testing to select the best chemotherapy drugs and combinations for each patient.

As the president said, drugs that work for one patient may not work for another, even if both patients have exactly the same diagnosis. This is why each patient should be tested to select the most effective and least toxic drug regimen for that individual before initiating treatment. It is an approach that the cancer industry now must adopt.

A Deep-dive Into Specialty Pharma

A specialty drug is a class of prescription medications used to treat complex, chronic or rare medical conditions. Although this classification was originally intended to define the treatment of rare, also termed “orphan” diseases, affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US, more recently, specialty drugs have emerged as the cornerstone of treatment for chronic and complex diseases such as cancer, autoimmune conditions, diabetes, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS.

In order to determine the best combination or sequence of drugs, I believe the cancer industry should apply human tumor explant analyses like our ex vivo analysis of programmed cell death. This provides a dynamic assessment of cancer cell response using each patient’s living cancer cells to select chemotherapy drugs. While the concept may seem new to some, we have successfully applied this technique in over 10,000 patients—many with difficult-to-treat cancers—and doubled their chance of response.

One reason this works, as the President has noted, is because each cancer patient is unique and the response to therapy is very different from one person to the next. When patients are treated without testing, the treating physicians must rely on general guidelines and protocols that cannot capture each patient’s individual features.

Ex vivo analysis of programmed cell death is distinctly different from the tests offered by most medical centers that rely upon DNA profiles known as genomic analyses. These use the patient’s chromosomal material to look for mutations and other changes in each patient’s gene makeup that might guide drug selection. Although the concept is appealing, in reality, only a minority of patients have genetic changes that can actually be used for therapy.

Each human cancer reflects all of its genes, both mutated and normal, acting together to create what we recognize as a malignant tumor. Only functional analyses can capture each patient’s tumor in real time and provide insights that can inform drug selection and treatment decisions.

In one study we conducted in metastatic lung cancer where the average response rate is 30% with traditional, generic treatment, patients had a 64.5% (p<0.001) response rate when they received drugs that were selected for them in the laboratory, pushing their survivals from months to years.

The role of the laboratory and functional profiling is to ensure that the most effective, least toxic treatments are selected the first time. This improves the likelihood of response and can help avoid toxic treatment choices when other milder drug combinations appear effective.

The broad application of this technology has the potential to improve patient outcomes, curtail costs, limit futile care and streamline drug development. We agree with President Biden that we need to change the way we treat cancer. Human tumor explant analyses may be just the answer the president is seeking.

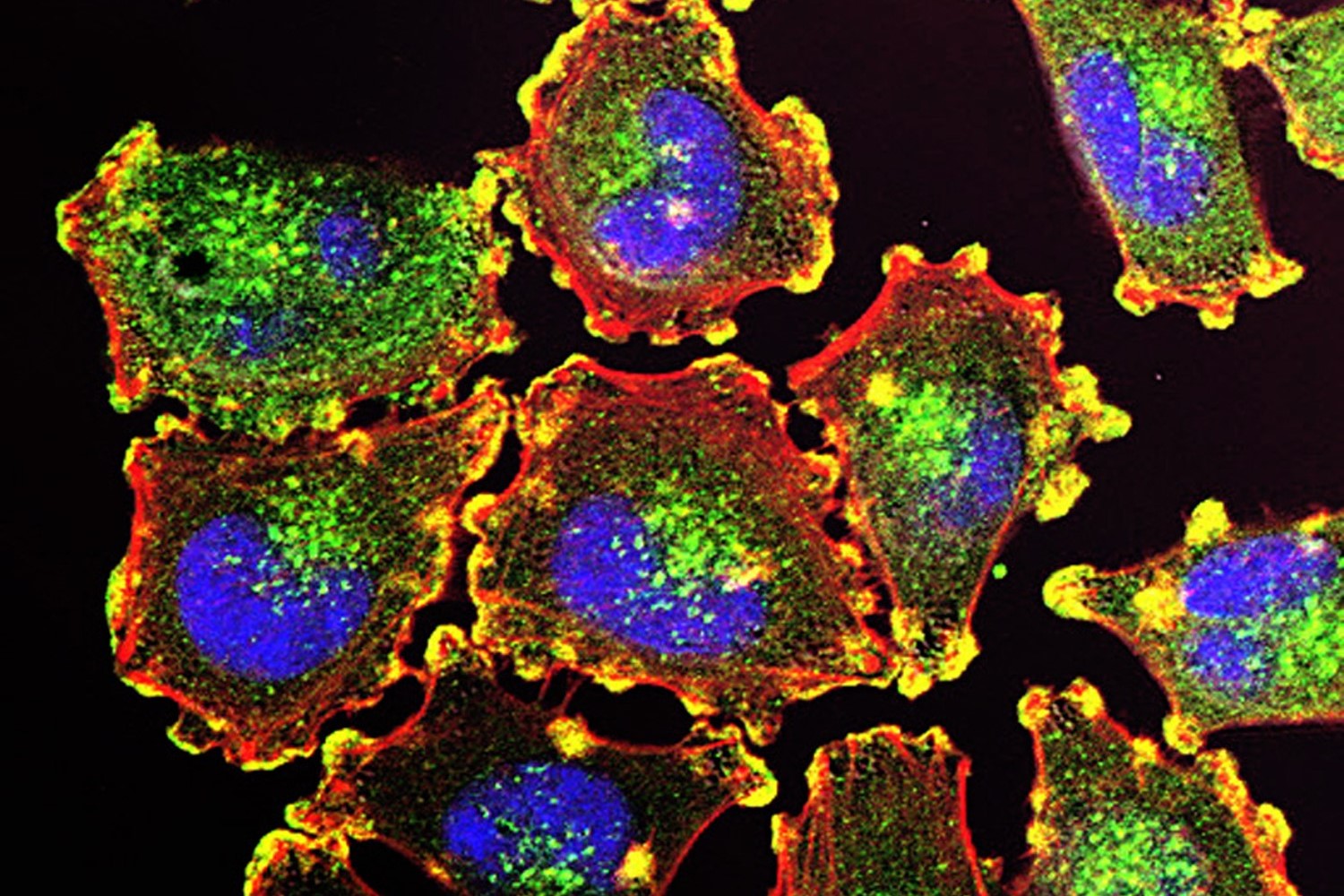

Photo: Julio C. Valencia via the National Cancer Institute

Dr. Robert Nagourney is an internationally recognized pioneer in cancer research and personalized cancer treatment.

With more than 20 years of experience in human tumor primary culture analyses, Dr. Nagourney has authored more than 100 manuscripts, book chapters, and abstracts including publications in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, Gynecologic Oncology, and the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Over the past 20+ years, Dr. Nagourney and his team at the Nagourney Cancer Institute are specialists at functional profiling, which measures how cancer cells respond when they are exposed to a wide variety of drugs and drug combinations.