After a bruising run of 14 years on the frontline, I am not here to tell you about my predictions for healthcare or why it is time to invest in healthcare cybersecurity; no, I am here to advocate for urgent reform of our hemorrhaging health-system model to make it fit for 2023 and beyond.

This bleeding out is despite $165.2B invested globally in digital health over the past five years and widespread steps taken to transform health systems by bringing in new allied health professionals, and implementing new clinical triage platforms, new communication platforms, new operating systems and new remote monitoring tools. All of these promised to make things better for patients and healthcare professionals alike. But they have not made sufficient headway in solving the biggest problems on the frontline. Hit by a growing workforce shortage, a huge administrative burden and widespread system inefficiencies, our health systems have reached the point where the proverbial wheels have finally come off the bus. Only a model that can properly marry access and quality will meet the scale of the crisis.

Health Benefit Consultants, Share Your Expert Insights in Our Survey

Dr. Namrata Rastogi Namrata is an MD, Family Medicine Physician, with an MS in Management from Stanford GSB. She has over 14 years of experience in healthcare executive and advisory roles: including VC, Product advisor to startups, Partner of a primary care clinic and Digital Transformation leader for a health system. She currently serves on […]

In the UK, National Health Service (NHS) ambulance response times increased across all categories from 2018-2022. Damning reports from 2021 estimated that around 160,000 patients per year were at risk of potential harm from queuing for over an hour in the back of an ambulance or in a hospital corridor. Although 2023 ambulance response times show signs of improvement, I have personally heard stories from General Practitioners (GPs) who have been left with no choice but to drive their patients to accident and emergency (A&E). In A&E, 30-45% of patients waited for over four hours to be seen by a clinician in October 2022, and record numbers of patients waited more than 12 hours for a decision regarding their admission to hospital (54,500 in December 2022, up 44% from the preceding month). The percentage of patients referred to secondary care with suspected cancer and seen within a target of two weeks, dropped to an all-time low of 72.6% in September 2022 and some patients waited over two months. From 2019-2022, the number of people waiting for treatment increased from 4.3 million to 7.2 million. The median wait time to be seen by a specialist increased to 14.4 weeks, and alarmingly, the number of people waiting for over a year to be seen grew 239 times larger.

The reality is that the health system crisis is universal. In the U.S., reports estimate that 90% of nurses are considering leaving the profession in the next year. Feeling undervalued, being under too much pressure and feeling exhausted are the main reasons. The same situation is mirrored in Australia. In my UK practice, I regularly care for nurses who, after giving their all for almost three years, have no more fuel in the tank. Clinician burnout hits home with me, with the death of my colleague, fellow GP, Dr Gail Milligan who sadly took her own life last year. It was clear from her husband’s account that this tragedy was the result of a sustained unmanageable and overwhelming workload. Unacceptable levels of clinical, administrative and business running responsibilities mean that 40% of GP partners are considering leaving for salaried roles.

Workforce shortages are leading to an increase in the proportion of contract or locum-based nurses and doctors, commanding higher median salaries resulting in increased health system costs. Rising costs of labor, drugs, medical supplies and equipment mean that over the next seven years, annual health expenditures in the US are expected to increase from $4 trillion to $8.3 trillion. This surge, combined with lower reimbursement rates, financial challenges from the pandemic and aging infrastructure, mean that 631 US rural hospitals (30%) are at risk of closure. Implications include reduced access to care, patients traveling further for care and potential delays in treatment. In turn, Americans are facing an affordability crisis – the average premium for an employer-sponsored family health insurance policy reached $22,221 in 2021.

The introduction of allied health professionals into health systems has diversified the healthcare workforce, bringing in a team with a broad skill mix to fulfill roles previously fulfilled by doctors as well as new additional roles. Examples of such roles in primary care include first contact physiotherapists, community pharmacists and physician associates. Whilst in the short term this strategy increases on-the-day access for patients to a health professional, the long-term benefits for payers and practices are less clear. In a value-based health system, how quickly the loop is closed on a patient-care-journey matters. For example, a patient who is booked with a physiotherapist for an examination, followed by a pharmacist for a painkiller prescription and then with a doctor for an x-ray request, is not saving any health system time or money when each of these activities could have been completed by the doctor in one appointment. How health systems optimize use of their new skill mix is still to be evaluated and refined.

A Deep-dive Into Specialty Pharma

A specialty drug is a class of prescription medications used to treat complex, chronic or rare medical conditions. Although this classification was originally intended to define the treatment of rare, also termed “orphan” diseases, affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US, more recently, specialty drugs have emerged as the cornerstone of treatment for chronic and complex diseases such as cancer, autoimmune conditions, diabetes, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS.

Physician associates with just two years of training (after a bioscience degree), require support from a physician. One study promisingly reported no significant differences between physician associates and GPs (in the rates of re-consultation, rates of diagnostic tests ordered, prescriptions issued, or patient satisfaction), and concluded that physician associates were an acceptable, cheaper alternative to a GP. However, no account was made for the time taken by GPs to supervise the associate, issue their prescriptions, monitor patient progress, and to take medico-legal responsibility for the care their colleague provided. Contrary to what some professionals contend, I do not think that making the existing workforce work harder through squeezing out every last inch of capacity is a sustainable solution. A surgeon performing seven operations instead of five in one day may look great for the numbers but the surgeon performing two additional procedures a day will likely become fatigued and introduce errors.

Even with U.K. government plans to recruit 50,000 more nurses by 2024, it will not be enough, as this number barely exceeds the loss of 40,365 nurses that left the NHS in the year to June 2022. The £1 billion funding increase planned in England from 2023-2024 for adult social care and discharge planning to get people out of hospital sooner is simply a drop in the ocean. With this continued trajectory, where will health systems be in five years with an aging population and the rising need for more clinicians? Will we ever meet these requirements and make healthcare equitable for all?

Is an increasingly fragmented, private healthcare system the answer? I hope not. Is GPT3 or even GPT4 going to solve all our problems? Not any time soon. Is investing more capital in healthcare the only answer? Not quite. So, what are the possible solutions to this crisis?

Back in 2008, specialty and specialist doctor roles were introduced in UK hospitals to increase workforce numbers. Today these roles vary in experience, but require a minimum of four years full-time training, post medical school. These doctors can practice independently, with a license to prescribe and have a regulatory body. I believe that a similar competency level, which is shorter than GP training (currently five years full-time training, post medical school), could be introduced in primary care to increase workforce capacity, whilst also maintaining quality of care, and reducing the workload of colleagues.

But what role can tech play? In an ideal world, we would see robust AI clinical decision-making tools supporting professionals who have fewer years of experience. However, as Babylon Health discovered, AI is not yet ready to fully deal with the complexity of the physical, psychological and social factors that each patient presents with. But that does not mean dramatic efficiencies are not possible. Hours of unpaid overtime that could be given to patients – or back to professionals (to maintain a semblance of life outside healthcare) – is wasted parsing dense referral letters to extract relevant data and action points. We could eliminate both paper and prose altogether from healthcare communication such as discharge letters and referral letters. While such technology is emerging, it is in its infancy and has not been widely adopted. Wiping out duplication of data entry, and capturing and coding more data in the electronic health record (EHR) automatically would represent a giant leap in reducing health systems’ administrative burden.

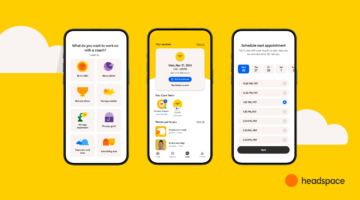

Whilst many may be subscribers to the virtual-first care thesis, such a model does have its limitations. To build an inclusive health system, patients will still need the option to pick up a phone or walk into a clinic. However, what we do know is that around 61% of people want to be able to access their health records from their providers’ EHRs via mobile apps or through an online patient portal. And therein lies the opportunity. We do not need to work more for patients. We need to enable them to do more for themselves.

Patients and their families are best positioned to decide the type of care they receive, when they receive it, and whether they wish to see an online or in-person provider. Amazon recently introduced Amazon Clinic, enabling customers to access a range of trusted, price-transparent providers through their platform. A similar NHS model could connect patients with NHS and private providers, expand the breadth of healthcare services available both online and in-person, and build an NHS platform that is as easy to use as Netflix. In this model, a basic rate of care is paid for by the NHS, and a higher rate of care is available to be paid for by the consumer, employer or insurer. Private ambulances can share the work with NHS ambulances. Non-traditional pathways of communication such as hospitals-at-home can communicate with meal delivery companies. Direct access to NHS secondary care specialists can be available for certain conditions and co-pay or insurance for others. Six sessions of counseling can be covered on the NHS, with the option to pay for more.

Whether it is within Amazon or the NHS, our health records could be held securely in the cloud, with each clinician or provider organization engaging with the record, and accountable for their own prescriptions and ongoing monitoring of the patient. The next step is to build a hub-and-spoke model where the ‘super provider’ such as the NHS becomes the hub platform. Approved provider organizations meeting quality, privacy and data protection standards, could access relevant patient data, and become spokes of the model. No single practitioner can be left with the ownership of patient care. The single point of truth should lie with the patient and their clinical record.

Namrata is an MD, Family Medicine Physician, with an MS in Management from Stanford GSB. She has over 14 years of experience in healthcare executive and advisory roles: including VC, Product advisor to startups, Partner of a primary care clinic and Digital Transformation leader for a health system. She currently serves on the Health Advisory Board at Palantir and as a Board Advisor at Medwise.ai.