Here are some core facts: Medicaid recipients experience lower access to care than Medicare or privately insured patients. Many factors play into care access, some being low Medicaid reimbursement rates, payment delays, and Medicaid’s billing process. There is also evidence that reimbursement rates are an essential determinant of healthcare utilization and health status among Medicaid recipients. These are just some of the many bureaucratic restrictions reducing access by limiting patient options, and they have typically been used to explain why many physicians are hesitant to take Medicaid and why some Medicaid recipients still struggle to access care as they face increased costs, wait times, and travel distances when seeking care.

Mental health challenges add to the problem. Nearly 40% of the nonelderly adult Medicaid population (13.9 million enrollees) had a mental health or substance use disorder (SUD) in 2020, according to a survey. Low reimbursement rates and a shortage of mental health professionals prevent people on Medicaid from getting the mental health care they need. Of the available providers, they do not have the capacity to see individuals promptly, resulting in long wait times. Ultimately, this forces many who cannot afford treatment to rely on the emergency room for help. Mental health services are becoming more of a privilege in a space where they should be a necessity.

With the Rise of AI, What IP Disputes in Healthcare Are Likely to Emerge?

Munck Wilson Mandala Partner Greg Howison shared his perspective on some of the legal ramifications around AI, IP, connected devices and the data they generate, in response to emailed questions.

According to Mental Health by Numbers, mental illness and substance use disorders are involved in 1 out of every eight emergency department visits by a U.S. adult, and 20.8% of people experiencing homelessness in the U.S. has a severe mental health condition; 37% of adults incarcerated in the state and federal prison system have a diagnosed mental illness, and 70% of youth in the juvenile justice system have a diagnosable mental health condition.

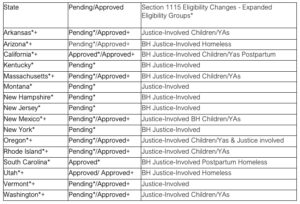

With these statistics, it is not too difficult to understand why we see a higher uptick in the 1115 waivers to address the justice-involved (adults and youths), waivers to address homelessness and housing, behavioral health, substance use disorder (SUD), severe mental illness (SMI), and serious emotional disturbance (SED). These 1115 waivers offer states a way to test new approaches in Medicaid that differ from what is required by federal statute.

So, how do we improve? Some findings imply changing financial incentives for providers could play an essential role in increasing access to care for Medicaid recipients. Research shows when it comes to primary care office visits, closing the gap between private insurance and Medicaid—a $45 increase in Medicaid payments for the median state—would close over two thirds of disparities in access for adults and eliminate such disparities among children. By understanding that reimbursement rates need to be addressed, California—among other states—is looking at additional modes to increase payment rates to providers.

We are starting to see a shift as Medicaid programs are undergoing an evolution to focus on whole-person, holistic care. This includes physical, behavioral, and social health needs by harnessing data and technology to identify vulnerable populations and coordinate proper care or services in real time to achieve improved outcomes. Medicaid plans leverage 1115 waivers to meet members where they are with targeted, integrated programs identifying those at most risk and working toward eliminating barriers to care, improving access, and addressing social determinants of health (SDOH) and health equity. Medicaid programs are in an excellent position to bridge the gap based on the demographic composition and physical health, behavioral health, and social needs of its beneficiaries. These waiver initiatives utilize pilots from community integration services supported by community integration services and specialized behavioral health services to help with and promote gainful employment, locate stabilized housing, combat substance abuse, and provide better mental health and substance abuse services.

The shift is quite evident as we review Section 1115 SDOH & Other DSR Changes. Approved SDOH provisions in states such as Arizona, Arkansas, California, Massachusetts, Oregon, and Washington focus on strong community, case management, outreach, educational, nutritional, and housing support. States are beginning to leverage waivers to strengthen their performance, provide whole-person care, improve operational efficiencies to reduce staff burden, and bring a sense of stability to a care delivery system that is constantly suffering from multiple stressors.

As we look at states leveraging Section 1115 Eligibility Changes (see table #1 below), take notice of a strong emphasis on the justice-involved, housing/homelessness, and behavioral health. On January 26, California became the first state in the nation approved to offer a targeted set of Medicaid services to youth and adults in state prisons, county jails, and youth correctional facilities for up to 90 days (about 3 months) before release. The reentry population faces complex barriers to healthcare and behavioral health access and often experiences homelessness, unemployment, and a lack of social and family support. Drug overdose is the leading cause of death after release from prison. Within the first two weeks after release, the risk of death from drug overdose is 12.7 times higher than in the general population, with the risk of death further elevated among females. People released from incarceration have an increased risk of adverse health outcomes and death due to preexisting behavioral health and chronic medical conditions and the negative effect of incarceration itself. These problems are barriers to healthcare and essential social determinants of health such as shelter, food, and employment. Some wrinkles need to be worked out for people involved in the justice system, especially surrounding the services that are provided 30-90 days before release. Things like notifications to the health plan explaining someone’s release or incarceration and/or issues that occur if the release date happens later than 90 days or before the expected release date are all challenges that still need to be addressed. We need to get to a place where the same philosophy for inpatient admissions is applied to incarcerated members including discharge planning (or transition of care) that begins on admission.

Waiver: Section 1115 Eligibility Changes – Expanded Eligibility Groups* Waiver: +Section 1115 SDOH & other DSR Changes+

Table#1

Studies show that wrap-around support, such as case management, outreach (crisis, education), counseling (financial, behavioral), legal services, transportation, family support, and independent living skills training help individuals stabilize their lives, improve clinical and overall well-being outcomes, have significant cost savings over time, decrease emergency room visits, and increase trust and engagement. An example is housing support; CalAIM provides security deposits with a lifetime cap. They understand the services needed to support secured housing, such as financial literacy, interventions for behaviors that may jeopardize housing, and continued non-clinical support services. CalAIM also supports short-term, post-hospitalization housing. Research shows interventions to prevent homelessness are more cost effective than addressing issues after someone is already homeless. The longer a person is unhoused, the more complex and expensive it becomes to re-house them. Rapid rehousing helps people move from emergency/transitional shelters or from the street into stable housing as fast as possible. It also connects people with supportive, community-based resources that help maintain housing.

Other states are taking similar steps to provide whole-person care: Massachusetts’ MassHealth will provide targeted support to its at-risk members in areas including nutrition and housing through the newly approved 1115 demonstration extension, while Oregon is leveraging the 1115 waiver to help eligible populations experiencing life transitions maintain access to medical care and related support services.

Looking at Medicaid only, in serving people with complex clinical, behavioral health, and social needs, state Medicaid agencies are uniquely positioned to identify and help address these diverse social challenges. In recent years, many of these agencies have developed strategies to support providers in addressing patients’ SDOH that complement more traditional medical care delivery programs. Some state Medicaid agencies have started integrating coverage for interventions focused on SDOH into new value-based payment models. Many Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) have also developed interventions addressing SDOH by linking clinical and non-clinical service delivery to improve health outcomes and cost efficiencies. There is a saying that your predictions are only as good as your data. Therefore, interoperability plays a significant role in organizing and effectively exchanging data between systems. Crucial and accurate data delivered at the right time, to the right people, supports the right decision!

As we advance, we must continue to be innovative, forward thinkers. We need to share best practices, lessons learned and pitfalls to address systemic inequities. To maximize an individual’s outcome, and ultimately a population’s, we must recognize the care we give is long term. It’s a journey, and it is our duty to meet each member—every minute, day, and year—where they are functionally, emotionally, socially, culturally, and spiritually.

Photo: zimmytws, Getty Images

Karen Iapoce, Senior Director of Government Solutions at ZeOmega, has 30+ years’ experience in strategic healthcare. Over the years, her titles have ranged from RN to Senior VP of Clinical Operations and Director of Government Solutions. Karen is a clinical leader, trainer, and liaison experienced in driving innovations in quality, products, metrics, revenue, and cost. She has expertise in Medicaid, Medicare, Social Determinants of Health, and federal/state regulations and their application within payer/provider environments.