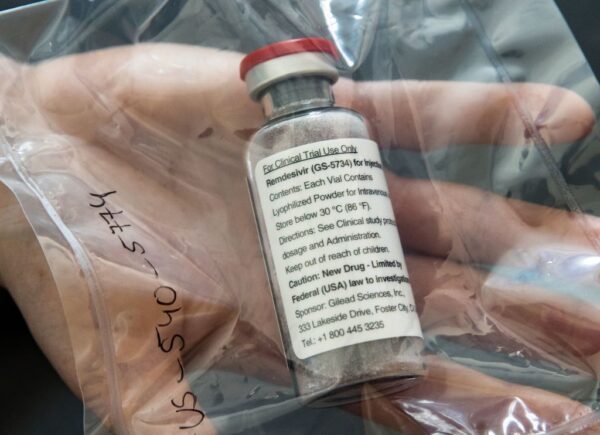

Last week, Gilead Sciences made significant adjustments to the Phase III trials of its drug remdesivir in hospitalized patients with Covid-19, leading to some speculation that the company may have lowered its expectations for the drug. Two investigators in the trials weighed in on what the changes could mean, as well as some of the challenges they have encountered in enrolling patients in the trial.

Foster City, California-based Gilead launched the two randomized, but non-blinded trials – testing standard treatment plus remdesivir given for five or 10 days – last month. One was a 400-patient study in severe disease that measured the proportion of patients with normalization of fever and oxygen saturation over two weeks. The other was a 600-patient trial in moderate disease measuring the proportion of patients discharged from the hospital in the same time frame.

But on April 6, the company increased the enrollment targets to 2,400 patients for the severe-disease study and 1,600 for the moderate-disease study. In addition, it changed the primary endpoints to measure patients’ odds for clinical improvement after 14 and 11 days on a seven-point scale that ranges from the patient dying to being well enough not to require hospitalization.

A Gilead spokesperson wrote in an email that the enrollment targets were adjusted to increase access to remdesivir and provide additional data, but did not address the question of why the endpoints were changed except to say that the change was unrelated to the enrollment target increase.

“The way I interpreted that is that they wanted to provide access to remdesivir while they were analyzing the data from the first part of the study,” said Dr. Debra Poutsiaka, an infectious disease physician and lead investigator of the study for Tufts Medical Center in Boston, in a phone interview, referring to the enrollment increase. “That’s how it was conveyed to us.”

In a note to investors, RBC Capital Markets analyst Brian Abrahams gave some potential reasons for why the endpoints were changed.

“We believe the changes improve alignment to the latest understanding of COVID-19’s course and should maximize sensitivity to detect any potential treatment effect, though they also imply that – perhaps based on data the company may be observing from ongoing experience with the drug – the magnitude of benefit, if any, is likely to be modest,” Abrahams wrote. He added that it would align with the view that like other drugs in development for COVID-19, remdesivir is more likely to have incremental benefit rather than being a panacea.

But Dr. Prashant Malhotra, lead investigator of the studies for New York City-area health system Northwell Health, said in a phone interview that the new endpoints still reflect the information sought for the ones that were previously used, with measures encompassing the spectrum of the patient dying to being well enough for discharge, along with some based on “statistical finesse.”

“I wouldn’t read too much into the change,” Malhotra said.

Poutsiaka added that the new endpoint is in line with the six-point scale recommended by the World Health Organization, with the addition of a seventh point specific to use of remdesivir. Other Covid-19 studies have used similar endpoints, such as the failed trial of AbbVie’s HIV drug Kaletra (lopinavir, ritonavir).

Despite the changes, Abrahams wrote that data from the Gilead trials is still anticipated in May.

But while it’s unclear whether it would affect the timing of trial data, both interviewed investigators said enrollment in the moderate-disease trial has been slower at their centers than that in the severe-disease trial, for several reasons.

The Gilead spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment about study enrollment. Neither investigator had the current enrollment number; Poutsiaka said the last figure she saw showed the moderate-disease study was less than one-third enrolled, but that was “weeks ago.”

Poutsiaka said that it appears many patients with moderate disease are simply staying home rather than going to the hospital – hospitalization is a requirement for taking part, and the drug is administered intravenously – even if they fit the study’s criteria for enrollment. The drug is intravenous, and hospitalization is required for trial participation.

“I think that the people who come into the hospital are by definition sicker, and that’s why we’re seeing more that would qualify as severe disease in the Gilead trials,” she said.

In New York, Malhotra said, the issue is that because of the extraordinary pressure the disease is exerting on hospitals – including being asked to increase capacity by 50% – some patients who would ordinarily be admitted for observation are instead being discharged or transitioned to home observation, thereby disqualifying them for enrollment into the trials.

As of Tuesday morning, New York City, a major epicenter of the pandemic, had 106,763 cases and 7,349 deaths, with the U.S. total far surpassing half a million.

But another factor slowing enrollment in the moderate-disease trial and even the severe-disease trial, Malhotra said, is that thanks to the publicity around the antimalarial drugs hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, patients who are admitted to the hospital are frequently put on those drugs and thus rendered ineligible for the remdesivir trials. Both studies’ exclusion criteria include participation in other clinical trials for Covid-19 treatments and “concurrent treatment with other agents with actual or possible direct acting antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2” less than 24 hours before remdesivir dosing. Malhotra explained that patients in the remdesivir studies must have received a positive diagnosis no more than four days prior to randomization, and together with the need to be off the other drugs thus shortens the window for possible enrollment.

“It’s anecdotal, but I do think it plays a role,” Malhotra said, adding that he had heard similar accounts from investigators at other centers.

Consenting patients has also been a challenge due to the need to avoid direct contact with them and concerns that the traditional paper forms could act as fomites that could spread the virus. Poutsiaka said TMC has adopted a completely remote process involving the investigator, an impartial witness, the patient and any family members and friends getting on the phone to coordinate consent, though the logistics of a phone call with four or five people are the “most difficult part” of the study. Northwell has adopted workarounds like calling patients’ legal representatives.

Photo: Ulrich Perrey, Pool/AFP, via Getty Images