When Omega Therapeutics pulled back the curtains for a peek at its work last summer, it revealed a new class of medicines that regulate genes and address “undruggable” targets. The startup has since offered some additional details about its plans and on Tuesday it unveiled $126 million to back a lead program making progress against an elusive cancer target, potentially paving the way for more drugs that work in the same manner.

Behavioral Health, Interoperability and eConsent: Meeting the Demands of CMS Final Rule Compliance

In a webinar on April 16 at 1pm ET, Aneesh Chopra will moderate a discussion with executives from DocuSign, Velatura, and behavioral health providers on eConsent, health information exchange and compliance with the CMS Final Rule on interoperability.

The new cash, a Series C round of funding, comes eight months after Cambridge, Massachusetts-based Omega raised $85 million.

Most drugs work by binding to a site on a target and either blocking that molecule from doing something or sparking a desired therapeutic effect. Like a light switch, they’re either off or on. Omega Therapeutics is developing medicines that it calls epigenomic controllers. These drugs are more like a programmable dimmer switch that can be set to dial the activity of a gene up or down.

“We tune it up or down to the right level, not on or off,” CEO Mahesh Karande said. “We tune it to the right biological level to resolve the condition.”

An Omega drug binds to three-dimensional structures on DNA called insulated genomic domains (IGDs). The company’s technology has identified about 15,000 IGDs that have been classified as drug targets. The gene-regulating drugs are fusion proteins, comprised of a targeting protein that directs the therapy to its genetic destination and an epigenomic effector that regulates the gene’s activity. This approach does not alter the genetic code or nucleic acid sequences. The Omega drugs are delivered via lipid nanoparticles.

A Deep-dive Into Specialty Pharma

A specialty drug is a class of prescription medications used to treat complex, chronic or rare medical conditions. Although this classification was originally intended to define the treatment of rare, also termed “orphan” diseases, affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US, more recently, specialty drugs have emerged as the cornerstone of treatment for chronic and complex diseases such as cancer, autoimmune conditions, diabetes, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS.

Omega announced its lead epigenomic controller candidate, OTX-2002, during the J.P. Morgan Health Care Conference. The drug aims to regulate c-myc, a gene whose excessive activity has been linked to the spread of up to 50% of cancers, according to Omega.

“When [myc] goes out of whack in cancer, it leads to proliferation of cancer cells and uncontrolled growth,” Karande said. “Those cancer cells become over dependent on myc and grow out of control.”

However, the myc protein has proven to be an elusive drug target. It doesn’t have binding pockets where small molecule drugs typically attach. Also, this protein is found on the inside of cells, making it unsuitable for drugging with antibodies that bind to targets on a cell’s surface.

Biotech companies have tried other ways to drug myc. Dicerna Pharmaceuticals of Lexington, Massachusetts, used RNA interference, an approach intended to stop a gene from producing a disease-causing protein. For a time, Dicerna’s myc drug was the company’s lead program. That candidate was a potential treatment for a hepatocellular carcinoma, a type of liver cancer characterized by amplification of myc. In 2016, the biotech stopped work on its myc drug, saying preliminary clinical results did not meet expectations.

Myc is a tricky target, and not just because it’s hard to get a molecule to bind to it. Healthy cells rely on the gene, too, so completely turning it off might stop its role in cancer but could also lead to problems elsewhere, Karande said. Rather than turning myc off, Omega’s approach tunes down the myc gene’s activity. Liver cancer is OTX-2002’s disease target. Karande said that the company wanted a liver indication because lipid nanoparticles have already demonstrated that they can deliver therapies to the liver. Furthermore, the company wanted a lead indication in oncology.

In preclinical research in hepatocellular carcinoma, Omega said its drug “potently downregulated” myc expression. The company is advancing its drug toward clinical trials, though Karande declined to say when human testing is expected to start.

Chief Financial Officer Roger Sawhney said that the new capital will support further development of Omega’s lead drug candidate. The company also plans to build a manufacturing site, giving the company both control and flexibility. Some of the funds will support development of the rest of Omega’s drug pipeline, which encompasses regenerative medicine, inflammatory disorders, acute respiratory distress associated with Covid-19, alopecia, neutrophilic dermatoses, non-small cell lung cancer, and an additional undisclosed oncogene target.

What Omega will not be doing is testing OTX-2002 against multiple cancers the way many companies assess their drug candidates. The IGDs that Omega’s drug targets are found everywhere in the body but Karande said that the same IGD will function differently in different tissues and cell types. That means a gene-regulating drug for lung cancer would require a different configuration than the one OTX-2002 uses for liver cancer. He added that Omega’s technology enables it to engineer these configurations quickly.

Omega’s latest round of funding included investment from Flagship Pioneering, the venture capital firm that founded the company and is its main financial backer. Other participants in the round included Invus, Fidelity Management & Research Company, funds and accounts managed by BlackRock, Cowen, Point72, Logos Capital, Mirae Asset Capital and other undisclosed investors.

Karande acknowledged that an IPO has crossed his mind, but he said Omega is looking at multiple ways to finance its work. Because the company’s technology is a platform that could support dozens of programs in many therapeutic areas, Karande said Omega is exploring partnerships with larger companies as another way to further advance the startup’s research.

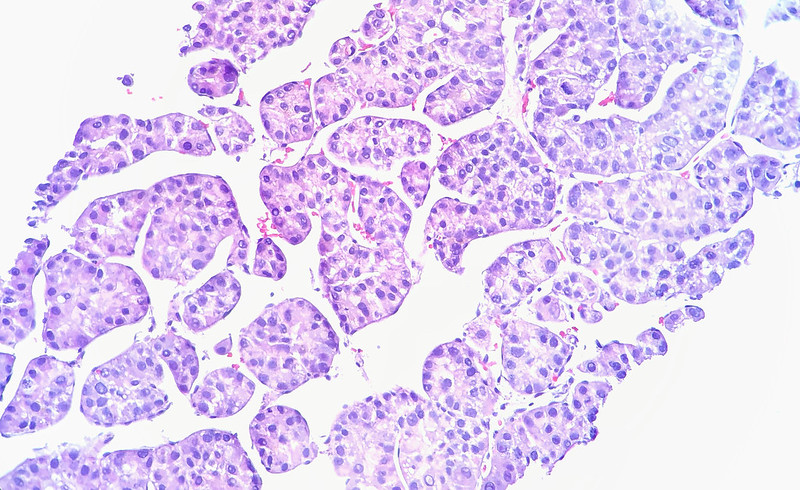

Image by Flickr user Ed Uthman via a Crreative Commons license