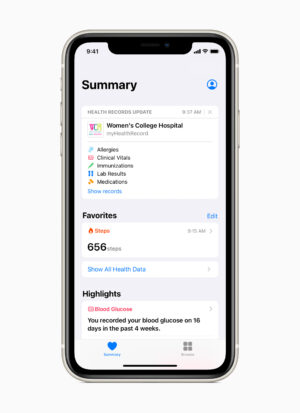

More than 700 hospitals and clinics have integrated with Apple’s health records feature. But how many patients are actually using it? Photo credit: Apple

Three years ago, Apple launched a new feature for people to pull in their health records with much fanfare — and some skepticism.

The company made its big debut not long after Microsoft and Google had shuttered their own personal record efforts. Apple brought in healthcare executives who touted the tool, claiming it would be a move toward “patient empowerment,” even as industry analysts were pointing out the limitations of building such a tool on an operating system used by less than half of the U.S. population.

Three years later, the question still looms: Will Apple succeed where its big tech brethren failed? It’s important to note that some believe that both Microsoft and Google’s personal health records efforts failed to scale because they weren’t tied to a particular provider. By contrast, Apple has drummed up 700 hospitals and clinics that have integrated its health records feature with their EHR systems, far beyond the initial 40 at launch. They include blue-chip health systems like Mayo Clinic and Cleveland Clinic.

On top of that, Apple clearly is still investing in the project. At its annual developer conference in June, executives announced plans to roll out a feature this fall that would let patients to share records with their doctor.

All of which sounds promising if people are actually using the Health Records feature to begin with.

A Deep-dive Into Specialty Pharma

A specialty drug is a class of prescription medications used to treat complex, chronic or rare medical conditions. Although this classification was originally intended to define the treatment of rare, also termed “orphan” diseases, affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US, more recently, specialty drugs have emerged as the cornerstone of treatment for chronic and complex diseases such as cancer, autoimmune conditions, diabetes, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS.

Perhaps predictably, Apple declined to say how many people are using the Health Records feature through its Health app. Neither did the company offer an executive or representative to speak on the record for this article. (Representatives did, however, explain the health records feature on background). As a result, MedCity News interviewed others to understand the technology, how many people are using it and in what manner.

Not easy to find

Apple’s health records feature lets people pull in records from their healthcare provider, including allergies, immunizations, vitals and lab results. Photo credit: Apple

Locating Apple’s Health Records feature isn’t exactly intuitive. It’s tucked away in the Health app on users’ iPhones.

From there, people must look up the hospital or clinic where they want to get their records, and remember their username and password for that provider’s patient portal. They have to repeat the same steps with each provider from whom they wish to access records.

This works well from a privacy perspective, as Apple doesn’t touch the health records at all. But the effort involved doesn’t bode well for adoption. While some people might be willing to go through all of these steps, many people can barely remember their login information for their hospital’s patient portal, if they’ve ever used it.

In a 2011 post-mortem of its own health records efforts, Google admitted that while it had won over some tech-savvy patients, caregivers and fitness enthusiasts, it hadn’t found a way to translate that into widespread adoption.

Even with its promises of privacy and enthusiastic fanbase, it’s unclear if Apple has cracked this code. Its health division has seen several recent departures, and Apple is reportedly scaling back a separate wellness app due to lack of engagement, according to Insider.

Provider integration

Though hundreds of health systems, hospitals and clinics have implemented Apple’s Health Records feature so far, providers have a thin grasp on its use.

For this article, MedCity News reached out to 30 health systems, hospitals, physician practices and companies and interviewed the six who agreed to an interview. They are:

- University of California San Diego Health in San Diego, California

- Hattiesburg Clinic in Hattiesburg, Mississippi

- Yuma Regional Medical Center in Yuma, Arizona

- ChristianaCare in Newark, Delaware

- Gunnison Valley Health in Gunnison, Colorado

- Laboratory Corporation of America Holdings in Burlington, North Carolina

A majority of the providers MedCity News spoke with did not have any data on usage, and UC San Diego Health — the only one that did — reported that adoption was low but seeing a little growth.

“What I can share, the numbers we have is fairly low,” said Marc Sylwestrzak, director of information services experience and digital health at UC San Diego Health Sciences, in a phone interview. “In October of last year, we were probably sitting at around 1,100, which is a small number. But, we have seen that [figure] more than double in the last 7 to 8 months…In June we were probably sitting at 2,300 or almost 2,400 unique patients.”

That number is a fraction of the 417,000 patients that UC San Diego Health System provided care for in the past 18 months. Remember also that UC San Diego Health was among the first health systems in the country to test the Health Records feature. If the earliest adopters are seeing such weak adoption of this feature, one can only imagine what the uptake rates are among patients at other systems.

While users have been hard to come by, it appears that at UC San Diego Health, an early survey from 2019 showed that at least those who used it found it valuable. In fact, 90% of users believed it facilitated better health information sharing and understanding of their health.

For providers too — those that chose to integrate the feature with the hospital’s EHR — the process was not a challenge.

“The implementation of Apple Health [Records] in 2018 was a straightforward process [for us] that took a few months,” said Randy Gaboriault, chief digital and information officer, at Newark, Delaware-based ChristianaCare, in an email.

In addition, EMR vendors, like Epic and Cerner, help make it an easy and technically secure process, he added.

Even smaller providers like Gunnison Valley Health in Colorado and Hattiesburg Clinic in Mississippi said the implementation was not difficult as they had guides they could follow.

On the whole, providers believe Apple’s Health app is a boon for patients. They said that it does empower the patient by bringing together information about their health from disparate sources, including from different providers and wearables like Apple Watches. This gives patients access to a wide array of data in real-time.

“It allows patients to have an active role in their healthcare as they are able to monitor certain health metrics and communicate those to their physician without having to make an appointment to see the physician,” said Renee Williams, senior system analyst, at Hattiesburg Clinic, in an email.

The multispecialty clinic, which includes 300 physicians, has received positive anecdotal feedback from patients about Apple’s Health Records feature, Williams said.

Despite a generally positive view of the app and the Health Records feature, providers are not actively promoting its use, leaving patients to either find Apple’s Health Records feature themselves — a challenge given how hidden away it is — or waiting until they ask about it.

Others want to promote their own patient portal instead. That perspective is espoused by Dr. Sarah Kramer, chief medical information officer of Arizona-based Yuma Regional Medical Center. She believes it is more important to have patients use the hospital’s patient portal. The portal allows patients to schedule appointments, message their care team, pay their bills and view clinician notes, none of which is currently possible through Apple’s Health app under which the Health Records feature sits.

“Apple Health [Records] has a lot of promise, but in my mind, it’s really up to Apple to market that,” Kramer said in a phone interview. “Once we have our patients signed up on MyChart, our preference is that they use that.”

Even larger organizations like LabCorp are driving patients to use their app over Apple’s Health app.

“We do a pretty thorough job about letting them know about the LabCorp patient app,” said Lance Berberian, LabCorp’s chief information and technology officer, in a phone interview. “We put less attention on the Apple Health app.”

The LabCorp app also provides more capabilities than Apple’s Health product, including enabling patients to make payments.

App integration is useful in other ways

While usage data is either scant or underwhelming, undermining the “patient empowerment” narrative forwarded by Apple, some providers are finding the data collected through the Health app itself to be useful. This is of increasing importance now as hospitals and health systems push into remote patient monitoring and other at-home services.

For example, UC San Diego Health is conducting a remote patient monitoring program that leverages data from the app. Patients using wearables and devices, like blood pressure monitors and glucometers, record data via the app and then share it with their care team through Apple’s integration with Epic’s MyChart patient portal, UC San Diego Health’s Sylwestrzak said. So far, about 500 patients are participating in the pilot.

“Once the data is received by UCSD…the data is used to cohort patients into a dashboard, alerting a multi-disciplinary care team to follow-up with patients as needed,” he said.

Apple’s Health app supports a large number of data elements, and it is easy to use, he added. The health system is planning to expand the pilot.

Similarly, Hattiesburg Clinic is in the early stages of utilizing Apple’s Health app for home blood pressure readings, glucose monitoring and weight management with a small percentage of patients, the clinic’s Senior System Analyst Williams said.

Technical limitations

It’s difficult to assess how much of a health benefit users derive from the Apple’s Health app. Since it’s built using the FHIR standard, the app is capable of pulling in structured data, but is limited in its ability to pull in unstructured data, such as notes or imaging.

As it’s currently designed, the Health Records feature pulls health information and categorizes it into seven segments, including allergies, vitals, health conditions, immunizations, lab results, medications and procedures. Separately, the Health app also includes information pulled in from wearables, such as users’ heart rate or sleep. Users can view their lab values over a period of time, such as LDL cholesterol, and see if it was in-range.

This could be helpful for people to get a baseline of their health, or share allergy information with a new doctor. But for people managing complex conditions with lots of records, such as cancer, it only scratches the surface.

“Apple is a breadth play — we can only do a little bit but we’ve got to do it for hundreds of millions of people,” said Anil Sethi, Apple’s former director of health records. Sethi has started his own health record startup, Ciitizen, after his sister Tania was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer and he became keenly aware of the limitations of current records companies. For example, things like pathology reports, imaging, and information on a tumor’s size and grade normally can’t be pulled in through the API.

“Apple uses tech to get whatever the tech will supply through the API. That’s about 8% of all the onco-information that Tania needed,” he said.

Sethi’s new company is taking a different approach, helping a smaller number of people get much more of their data, by requesting it using patients’ right of access under HIPAA and then organizing it in a readable format.

Sethi is not the only one who sees limitations in Apple’s approach.

Ardy Arianpour, who founded a startup that seeks to be the “Mint.com of health records,” said Apple misses some information by only focusing on FHIR data.

“95% of the data out there is non-FHIR,” he said. “It’s not that FHIR is bad. It’s just that FHIR is not special.”

Arianpour’s company — Seqster — built a system to quickly pull patients’ records from multiple facilities using an identifier, such as a driver’s license or social security number.

Yet he credits Apple for shining a light on the issue of personal health records.

“What Apple has done is free advertising for how important this market is,” he said.

While Arianpour and Sethi find Apple’s Health app leaving much to be desired, others believe Apple’s approach is the right one. One app, CommonHealth, is specifically designed to be the Android equivalent of Apple’s Health Records feature. Commons Project co-founder JP Pollak said the company picked this approach because it’s good from a privacy perspective — the data is pulled directly to users’ devices without being processed in the cloud — and it’s the easiest to scale to a large number of people.

“The mechanism of connecting people directly with the institutions that hold their care seems to be the best and most scalable model,” he said, “even if people have to remember their usernames and passwords.”

Future plans

In the long-term, Apple and its peers are betting that expanded access to data, and the ability to share it, will turn these apps from a nice-to-have into a must-have.

This fall, with the release of its new operating system, Apple will roll out a feature for users to share their health data with others, such as a caregiver or doctor. For example, their physician could review trends in exercise and sleep, or if a fall had been detected.

As providers ramp up remote patient monitoring and other at-home services, this data can play a role in clinical outcomes. But leveraging it may not be as simple as it seems.

Pollak, who is working on a similar feature for CommonHealth, said this is a “really thorny issue.”

The challenges range from dealing with the intricacies of embedding that information in an EHR, to figuring out how to make data generated from smartwatches and other sources useful.

“Doctors don’t want to be inundated with data that’s not actionable,” he said.

While the pandemic provided to be a boon to the adoption of digital health, it still remains to be seen what has staying power beyond telemedicine tools. Providers may find Apple’s Health app and other features added on to the Health Records capability enticing, but it remains to be seen if the app’s intended beneficiaries will flock to it: patients.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect that the ability to pull in data from wearables is part of the Health app, separate from the ability to pull in seven categories of health information from healthcare providers under Apple’s Health Records feature.