Algorithms play a significant role in our daily lives — they unlock our phones, tell us which movies to watch and dictate the content we see on social media. These calculations are also frequently used by healthcare providers to inform diagnosis and treatment plans, so it’s important to remember that algorithms are only as good as the data used to train them.

Much of the data used to train today’s healthcare algorithms reflects the structural racism embedded in the U.S. healthcare system, creating a bias that negatively affects health outcomes among already marginalized populations. That’s why the engineers building healthcare algorithms should move away from using race as a measure of health disparities and pivot to using social determinants of health, according to the speakers featured on Philadelphia Alliance for Capital and Technologies’ Monday virtual panel on medical AI bias.

“Bias is present in the world. And if it’s present in the world, it will be present in the data,” said Seun Ross, Independence Blue Cross’ executive director of health equity.

When this biased data is used to train healthcare algorithms, the healthcare industry’s structural racism is perpetuated. To illustrate this point, Ross brought up an example of racist bias that has been historically present in the U.S. healthcare system: when Black and White patients present the same behavioral health symptoms, Black patients are more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia and White patients are more likely to be diagnosed with mood disorders like depression and anxiety. If engineers use historical health records of Black patients being treated for schizophrenia in the U.S. to train a machine learning program, it would arguably use racist predictors for its calculations and continue to over-diagnose schizophrenia among Black patients, Ross said.

Another panelist agreed.

Algorithms will continue to preserve the racial bias that has been historically baked into the U.S. healthcare system unless the medical field stops operationalizing race in its machine learning models, said Dr. Jaya Aysola, assistant dean of inclusion and diversity at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

A Deep-dive Into Specialty Pharma

A specialty drug is a class of prescription medications used to treat complex, chronic or rare medical conditions. Although this classification was originally intended to define the treatment of rare, also termed “orphan” diseases, affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US, more recently, specialty drugs have emerged as the cornerstone of treatment for chronic and complex diseases such as cancer, autoimmune conditions, diabetes, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS.

Dr. Aysola co-authored an article last year in The New England Journal of Medicine declaring race is not a biological category based on innate differences that produce unequal health outcomes, but rather a social category that reflects the effects of unequal social experiences on health. She and her co-authors argue that medical education and practice have failed to evolve to reflect these advances in understanding the relationships among race, racism and health.

“If we start to see health differences by race, but we know that’s not intrinsic to genetic predisposition, a lack of personal agency or anything innate to that individual population, we have to ask the next question: well, then, what is the difference? What is race a proxy for?,” Dr. Aysola said. “And when we start to look at that, we realize that race is truly a proxy for structural racism.”

The idea that someone’s race would make them predisposed to a certain health condition is a fundamental misunderstanding, as race is social construct, according to Ross and Dr. Aysola.

Genetic ancestry — which is a biological feature, unlike race — can sometimes play a role in a patient’s likelihood to be diagnosed with a certain condition. But the real variable that machine learning models should be accounting for is the unequal treatment that a patient can receive as a result of structural racism, as this often has significant impacts on their health outcomes.

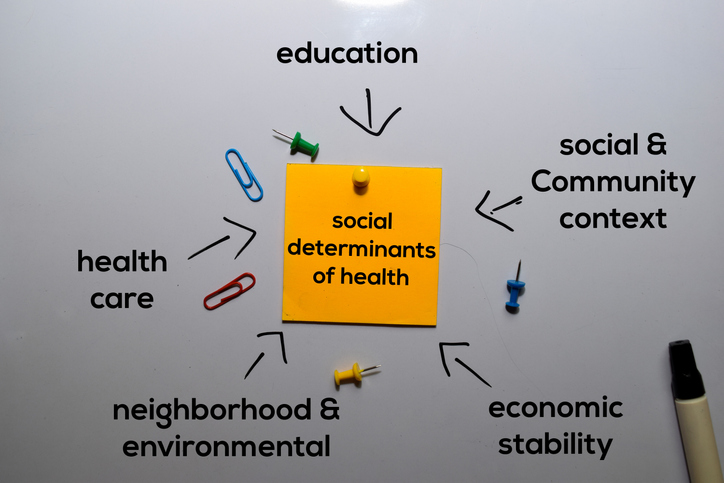

“Instead of using race as a measure for health disparities in research guidelines and standards of care, I think we should use social determinants of health,” Ross said. “Factors like whether or not you have health insurance, your neighborhood, education, occupation, income, wealth, health behaviors, sexual identity, gender, disability status, age and how you experience racism are the more important factors.”

Photo: syahrir maulana, Getty Images