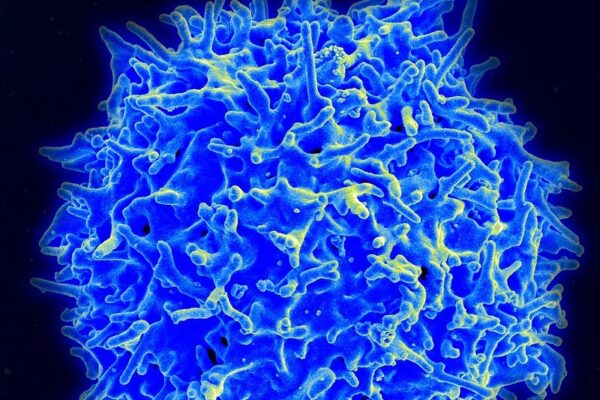

Patients whose blood cancer advances after initial treatments have one last therapeutic option: the engineering of their immune cells into a living medicine. But cancer is crafty and it often finds a way to evade this cell therapy too. Cargo Therapeutics is developing new cell therapies that overcome escape mechanisms, and it now has $200 million for their development, including a lead program on track to begin a pivotal clinical trial in the middle of this year.

Currently available cell therapies are engineered to target cancer by homing in on a cancer protein called CD19. As long as cancer cells express that protein, the CAR T-therapies can find them and kill them. Cancer cells defend against this targeted attack by “losing” the CD19 antigen, leaving a cell therapy with nothing to target. Consequently, about 60% of patients treated with a CD19-targeting cell therapy either don’t respond to treatment or they relapse, Cargo CEO Gina Chapman said.

“That group is growing because access to CAR T is growing around the world, and it’s also moving into earlier lines of therapy,” said Chapman, a veteran of Roche and Gilead Sciences.

The solution of San Mateo, California-based Cargo is a CAR T-therapy that goes after a different target on cancer cells called CD22. Lead Cargo cell therapy candidate CRG-022 was invented in the lab of Crystal Mackall at the National Cancer Institute. The institute conducted the first test of this therapy, a Phase 1 clinical trial enrolling children and adults whose B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia had advanced after earlier treatment with a CD19-targeting immunotherapy.

Mackall brought the CD22-targeting program with her when she came to Stanford in 2016, where her roles include serving as the founding director of the Stanford Center for Cancer Cell Therapy. She founded Cargo, initially known as Syncopation Life Sciences, with Stanford colleague Robbie Majzner and Nancy Goodman, CEO of Kids v Cancer. Chapman said the trio presented the company’s science to Samsara BioCapital, which provided $11 million in seed financing to get the young company up and running in 2021. Cargo also has technologies from Stanford that are applied to the startup’s cell therapies.

Another Phase 1 test of CRG-22 is ongoing at Stanford, enrolling adults with advanced large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL). Preliminary data published in the journal Blood in 2021 showed that the first three patients treated with this cell therapy achieved complete remission. No toxicities were reported.

A Deep-dive Into Specialty Pharma

A specialty drug is a class of prescription medications used to treat complex, chronic or rare medical conditions. Although this classification was originally intended to define the treatment of rare, also termed “orphan” diseases, affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US, more recently, specialty drugs have emerged as the cornerstone of treatment for chronic and complex diseases such as cancer, autoimmune conditions, diabetes, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS.

Updated results were presented last month at the combined annual meetings of American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Of 38 patients dosed, 68% showed an overall response to the therapy; the complete response rate was 53%. Furthermore, of the 20 patients who achieved a complete response to the therapy, only one has relapsed. Toxicities were manageable and the median overall survival in all of the patients at this update was 22.5 months. Chief Medical Officer Gregg Fine said these results place Cargo in front of other biotechs pursuing CD22-targeting cell therapies.

“We’re addressing a growing unmet need, we have really strong data,” he said. “Durability is really important and we’re seeing that out of the Phase 1 trial.”

Cancer can develop many ways to resist therapies, and it’s here where Cargo aims to live up to its name. The company’s pipeline is comprised of therapies that place more cargo and more complex cargo on the engineered T cells, Chapman said. For example, the startup is developing multi-specific therapies capable of addressing more than one target on a cancer cell. Therapies will also have multiple components that enable them to overcome cancer escape.

CD22 is already the target of Pfizer drug Besponsa, an antibody drug conjugate (ADC) that won its FDA approval in 2017 as a treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). ADC Therapeutics is pursuing that target with ADCT-602, an ADC in early-clinical development for ALL.

In the realm of cell therapy, London-based Autolus Therapeutics is developing a multi-specific treatment in which T cells are programmed to target both CD19 and CD22. This AUTO1/22 program is in Phase 1 testing for ALL in children. Cellectis is going after CD22 with an allogeneic, or off-the-shelf, cell therapy it calls UCART22. This therapy, currently in Phase 1 testing, employs the TALEN gene-editing technology to get cells to express a receptor for CD22. The pipeline of cell and gene therapy developer Sana Biotechnolgy includes an allogeneic CAR T-therapy that targets CD22. The Seattle-based biotech is also developing a CD19-targeting cell therapy in which the engineering of immune cells happens inside the patient’s body. Both programs from Seattle-based Sana are in preclinical development for blood cancers.

Chapman acknowledged the allogeneic cell therapy research happening at other companies, but she said autologous cell therapies have been proven and there’s still lots of room for companies like Cargo to improve upon them. She added that Cargo’s technologies could be applied to allogeneic cell therapies and the company has an exploratory allogeneic program.

Cargo’s technology might also be able to address solid tumors, which so far have remained beyond the reach of cell therapy. Fine said that while CARs engineered to go after a single target have shown some activity against solid tumors, they probably need some additional enhancement to make them more effective.

“That’s where our ability to add more things to a T cell can really move the field forward,” he said.

The potential applications of Cargo’s technology drew the interest of a broad investor syndicate. Third Rock Ventures, RTW Investments, and Perceptive Xontogeny Venture Fund co-led Cargo’s Series A funding round announced this week. The financing also brought on new investors Nextech, Janus Henderson Investors, Ally Bridge Group, Wellington Management, funds and accounts advised by T. Rowe Price Associates, Cormorant Asset Management, and Piper Heartland, as well as Samsara, Red Tree Venture Capital, and Emerson Collective.

With the new capital, Chapman said Cargo plans to bring its lead program into a pivotal Phase 2 study enrolling patients whose LBCL has relapsed or has not responded to CD19 CAR T-therapy. The company will also evaluate the cell therapy in children who have B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Chapman expects the Phase 2 test will have interim data in mid-2024. She said the new capital will also support the next drug candidate in its pipeline, which will be multi-specific and have multiple components. An investigational new drug application is planned for the first half of next year.

Cargo is also looking for potential partnerships. Those collaborations could mean working with companies that can help Cargo improve the durability of a cell therapy, making it last long enough to work in solid tumors, Chapman said. These deals could also involve other companies making use of Cargo’s technologies for packing more stuff onto a T cell.

“We may not solve it, but we can also help others solve it as well,” Chapman said.